By Joel Turpin, ATP/CFII/FAA Master Pilot

INTRODUCTION

I realize that my readership consists mostly of airplane owners who fly for fun and recreation. But did you ever wonder what it would be like to get paid to fly a multi-million-dollar, turbine-powered airplane? In this article, I will give my loyal audience a glimpse of what the professional pilot does, and the challenges he or she may face.

There are many differences between flying for recreation and flying for a living. The most obvious difference is the type of airplanes we fly. A more subtle difference is what your boss expects from you as a pilot. There is no such thing as personal minimums in the arena of the professional pilot. Your boss expects you to be able to hand fly to the minimums on the approach chart and to the limitations set forth in the airplane flight manual. There is another more subtle difference and that is in risk management.

Flying to another airport for the hundred-dollar hamburger on a Sunday afternoon is not mission critical, but getting your boss back to home base in his 5-million-dollar airplane that he pays you to fly is mission critical. And this is where the difference in risk management (ADM) comes into play. The mindset for the hamburger flight is to look for any reason not to fly, such as crosswinds, low ceilings, rain, etc. The professional pilot looks for ways to fly while managing the risk. This difference is clearly illustrated in the description of a flight I made on March 16, 2025, flying the single engine, turbine powered Pilatus PC-12NG from Key West, Florida, KEYW, to Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania, KMPO. It would be a flight of 1,111 nm, or 1,278 sm.

FLIGHT PLANNING

I began flight planning by going on ForeFlight the day before and again on the departure date. I checked the weather forecast for Key West, Mount Pocono, and my planned alternate, Allentown, PA, KABE. I also checked for SIGMETS, AIRMETS, NOTAMS and more. The only NOTAM of significance was higher approach minimums for Runway 24 at Allentown, our filed alternate.

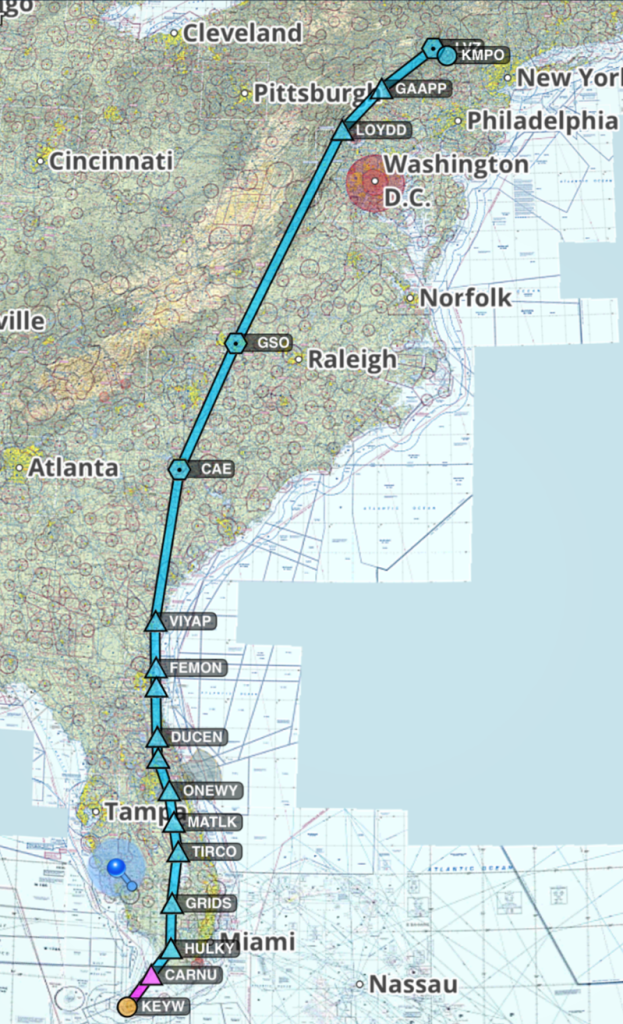

I then went on FltPlan.com to find the best route, optimum flight level, and what my fuel burn would be. I always file the route I am most likely to get rather than the one I want. Getting a route completely different than the one filed may result in not having the legal amount of fuel to make the flight.

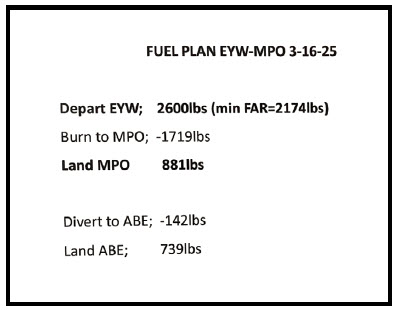

On FltPlan.com I selected the route I have always gotten in the past, thus almost assuring I would hear, “Cleared as Filed” from Key West Ground Control. There were four choices offered for flight levels, and I chose FL250 as a compromise between flight time and fuel burn. I filed that route and altitude, then recorded what the fuel burn would be. Next, I composed a fuel plan to go along with my flight plan to assure I would have the minimum legal fuel and adequate reserves not only at my destination, but also at my alternate as well.

Turbine engine fuel consumption is based on pounds per hour instead of gallons per hour, as with piston powered airplanes. My Pilatus burns on average 500 lbs per hour, or about 75 gallons per hour, with jet fuel weighing 6.75 lbs/gallon. With full fuel tanks, I departed Key West with 2,600 lbs of fuel, or about 5.5 hours endurance. Flight time was 3 hours and 57 minutes. On this flight, we will have a significant tailwind all the way to Mount Pocono which will allow for a little over 1.5 hours reserve at the destination.

The next step in flight planning was to conduct a weight and balance check which showed we would be under max gross and well within the CG limits.

THE WEATHER

The weather at Mount Pocono, KMPO, upon our departure from Key West, was a ceiling of zero and a visibility of less than 1/8th mile. The forecast was suggested to remain below approach minimums all day. This meant an almost certain divert to Allentown, our alternate. So, we made mental plans for my boss and his family to take an Uber from KABE to KMPO and that I would stay in KABE until the weather rose above minimums, then fly the plane home solo.

THE FLIGHT

There was a significant low pressure system just to the west of our planned route. This was good news and bad news. The good news was that it created a strong southerly flow and a subsequent tail wind at FL250 all the way to KMPO.

The bad news was those strong winds aloft meant turbulence, which we ended up being in for the entire flight.

THE APPROACH AND LANDING

Naturally, we checked the KMPO weather many times along our journey north. However, just 25 minutes south of KMPO, the weather miraculously rose to 700 OVC, with a visibility of 2 miles in rain with the surface winds from 170 degrees at 25, gusting to 35 knots.

Our only choice for an approach was the RNAV to Runway 13. This meant an instrument approach and landing with a significant crosswind in heavy turbulence.

MY FLYING SKILLS GET TESTED!

We were working with Wilkes-Barre Approach Control for our approach to the uncontrolled KMPO. At 4,000 feet we were flying in moderate turbulence when we got cleared for the RNAV/GPS RWY 13 approach. In fact, the turbulence was so bad I decided to let the autopilot fly the approach, something I usually do not do. My decision was based on the fact that the autopilot would fly the plane more smoothly in turbulence than if I hand flew the approach.

We intercepted the final approach course and the LPV glidepath at 4,000 feet and started inbound with the airplane and its occupants being assaulted by the turbulence. Over the final approach fix, I noted the winds aloft at 3,400 feet MSL (1,480 feet AGL) were out of the south at 55 knots! I also noted that the autopilot was using a 30 degree right crab angle to remain on the LNAV course, at an indicated airspeed of 130 knots. At about 600 feet AGL and about 2 miles from the runway threshold, my boss, who was in the right seat, and I saw the runway through the rain. It was now time to disconnect the autopilot and see if I had the skills to land in those conditions.

Crossing the threshold with the airplane a little out of control due to the turbulence, I did my best to set up for a crosswind landing. During the flare, I only had partial control but just enough so that I could make the crosswind landing. After clearing the runway, the wind gusts snapped the control wheel from my hands and slammed it from stop to stop. This required us to install the gust lock during taxi, thus ending a typical day in the life of the professional pilot.