By Joel Turpin

One of the more challenging maneuvers while flying on instruments is the missed approach. Arriving at the missed approach point while still in the weather requires a complete change of strategies, from landing to going around. Since your immediate future has just undergone a dramatic change, a new mindset is required.

This sudden and unexpected change to your flight requires a steady hand at the controls and a complete mastery of what you are going to do next, all while maintaining your mental composure.

We have all heard our instrument instructors tell us to assume that every approach will end with a miss. Missed approaches are exceedingly rare, and after hundreds of successful landings from instrument approaches, it is difficult to maintain the urgency of this mindset. So, let us investigate what is required to fly a safe and stress-free missed approach.

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

What can cause a missed approach?

Not all missed approaches are the result of arriving at the missed approach point and not seeing the runway environment. Misses can even occur before reaching the missed approach point. They can be the result of, but are not limited to, the following:

- Loss of ground-based signal, such as the localizer or glide slope going off the air.

- Being out of position laterally or vertically for a safe landing.

- Losing sight of the runway after seeing it prior to reaching the threshold.

- Losing sight of the runway during a circling maneuver.

- A mechanical problem such as an unsafe gear indication.

- ATC instructs you to go miss.

- An un-stabilized approach.

What constitutes the missed approach point?

Before flying an instrument approach, it is imperative that pilots know precisely what the missed approach point is. After all, how do you know it is time to go around if you don’t first know where this occurs? Ask yourself, what delineates the missed approach point on the approach chart? It could be based on time, DME, altitude as with a DH or DA, or an RNAV waypoint.

When to fly the published missed approach procedure

Among instrument rated pilots, there is some confusion as to when you are required to fly the published miss. The answer is simple; only when you are flying in a non-radar environment. It is true that when cleared for an instrument approach, you are also cleared to fly the published missed approach procedure. However, the only time you should exercise this clearance is while operating in a non-radar environment.

Other times you might fly the published miss include:

- While operating in radar contact when instructed to do so by the controller.

- It you have experienced a loss of radio communications (This is the primary reason you are cleared to fly the published miss when cleared for the approach.)

- When requested by the pilot for training purposes.

These are the only times you should fly the published miss. Again, the published missed approach is normally a non-radar only procedure. Flying the published miss while under radar without receiving a verbal clearance to do so from ATC could get you a violation or worse, and here’s why.

First and foremost, the controller will not be expecting you to do this. At controlled fields with radar service, there are pre-set plans for missed approaches for every runway which are known only to the controllers. They may include instructions to fly a certain heading and an altitude to climb to, both of which may differ significantly from the published procedure. Second, the published miss does not take into consideration local traffic or approaches in progress to other runways.

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

How do you know you are operating in non-radar?

If in doubt, after making the decision to go miss, simply announce that you are on the missed approach. Here is an example of what to say: “Arrow 15256 is missed approach.”

If you are in non-radar, the controller will instruct you to fly the published missed approach. If in radar contact, you will receive a route or heading to fly, plus an altitude to climb to. What the controller says will answer the question about radar contact.

Published miss even in radar contact

Even while operating in radar contact, pilots should still be familiar with the published miss in case the controller is busy and assigns it to relieve workload. Another reason is that at some locations, especially where terrain is an issue, you could be in radar contact while flying the approach until descending below a certain altitude. At that point, you will no longer be in radar contact, but the controller may not inform you of this change. In the event of a miss, you will be required to fly the published procedure. This is another reason to use the exact phraseology mentioned above on every missed approach.

Why do published missed approach procedures appear on approach charts at airports where radar is always in use? The answer is very simple; in case of radar failure. The controllers need a backup plan in case the airport’s radar goes out of service, and the published miss is their safety net.

Flying the missed approach while in radar and non-radar contact

While operating in radar contact, the final controller will issue the discreet missed approach instructions for that particular runway. In a non-radar environment, you will be instructed to fly the published procedure. However, terrain clearance is predicated on beginning the miss at the designated missed approach point. If the decision is made to go miss before reaching the MAP, first fly to the missed approach point before making any turns. This could mean descending to the decision altitude on an ILS, LPV, or VNAV approach before initiating the missed approach procedure.

While it may seem to be counterintuitive, climbs from a missed approach must be made with caution as some procedures have climb restrictions. A dramatic example of this will be discussed later.

Aviate, Navigate, Communicate

When the decision to go miss is made, whether in radar contact or not, fly the airplane first, get established on the route or heading for the miss, then communicate with ATC. The instant you decide to go around is not the best time to tell the controller of your decision. Believe it or not, the declaration of a missed approach is not particularly time-sensitive, especially in a non-radar environment. This brings us to the most important part of flying the missed approach, which is how to do it safely.

During a missed approach, you will be flying very close to the ground while still on instruments. For example, a miss from an ILS and some LPV approaches will put you just 200 feet AGL while still on the gauges. Are you really ready to copy and understand what could be a lengthy and complex clearance with a handful of airplane while flying on instruments 200 feet above the ground?

What if the missed approach clearance includes holding instructions and an EFC?

Also, getting a mile-long clearance at machine gun speed while you are advancing the throttle, retracting the gear, the flaps, and setting climb power could result in a mental overload, and even a loss of control. Fortunately, there is a better, safer, and less stressful way to fly the missed approach.

Priorities!

Your first two priorities are 1) Getting the airplane established in a stabilized climb and 2) Flying away from the ground as quickly as possible. A good technique is to fly the miss at Vy for at least 1000 feet AGL, or until you are certain of being above any obstructions in the departure path.

Again, there is no hurry to inform ATC of your missed approach. Wait until you are established in a stabilized climb, with the gear and flaps up and climb power set before telling the controller you are on a missed approach. With no more levers or controls to manipulate, the airplane established in a climb, some altitude, and the autopilot on, you are now ready to copy the missed approach instructions and to comprehend them as well.

When you must descend after going missed approach

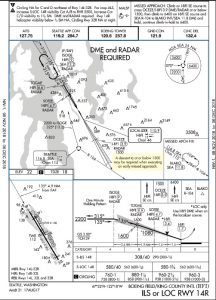

Instrument pilots should be aware that climb restrictions on the published missed approach exist at some airports. A good example of this is the ILS RWY 14R to the Boeing King Field, KBFI, near Seattle, Washington. King Field is located in close proximity to the Seattle International Airport, KSEA.

To avoid a traffic conflict with KSEA, the published miss at KBFI has a climb restriction on the published missed approach to cross the OCEZE intersection at or below 1500 feet before continuing to climb to 6400 feet, the top altitude. Initiating an early missed approach from above 1500 feet will require the pilot to first descend to 1500 feet or below until crossing the OCEZE fix before continuing to climb to the top altitude for the procedure of 6400 feet.

This is stated in very fine print at the bottom of the approach chart [members only], just above the profile view. Here is what it says.

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

Lessons learned

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

Flying the Obstacle Departure Procedure

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

Conclusion

This is an abbreviated non-member version. Log in and read the full version with charts here.

Joel Turpin started his flying career in 1966 by soloing in a J-3 Cub at age 16, and later earned his CFI as a 19 year old college student. After graduation, Joel became the chief pilot of a commuter airline where he flew the DC-3, Beech 99, and Beech 18 in scheduled passenger service. In 1978, Joel became the Director of Training for FlightSafety International’s King Air Division. He was hired by a major airline in 1986 where he flew the B-727, B-737, B-757 and B-767 in both domestic and international operations retiring at age 65 in 2015 with 28,000 hours in his log book. Joel currently flies a Pilatus PC-12NG for a corporation and teaches instrument flying in single engine airplanes. In 2016, Joel was awarded the Master Pilot Award by the FAA for 50 years of flying accident and violation free.