By Joel A. Turpin, ATP CFI-I FAA Master Pilot

Introduction

There are two kinds of pilots in command of an airplane regardless of its size. One plans a flight with the mindset of “What If?” – meaning what if something happens that was not in the original flight plan? Playing “What if?” means having contingencies if the flight does not go as planned.

Then, there is the other kind of pilot who plays the “I Hope Not” game. The “I Hope Not” pilot bets everything on the flight going exactly as planned, with no plan B in case it doesn’t. I will illustrate examples of both kinds of pilots in command based on my own personal experiences.

I Play “What if?”

It all began one evening in 2003 at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. I was the assigned captain on a United Airlines flight to San Diego, California flying a Boeing 757. I received the flight plan that my dispatcher had created and perused the maintenance history of my 757, the filed route, and the NOTAMS. All looked perfect for the four-plus hour flight, including the weather. The forecast was for clear skies with a light breeze out of the west for my arrival at about 10pm. The only thing that caught my eye was the landing fuel reserve my dispatcher had given me.

Because it was perfect VFR, I legally only needed a 45-minute IFR reserve, but the dispatcher had given me an extra 15 minutes for contingencies, making my arrival fuel exactly one hour, which was 7,000 lbs. for the 757 I would be flying. While this was all perfectly legal, I got into a “What If?” mindset when considering my fuel.

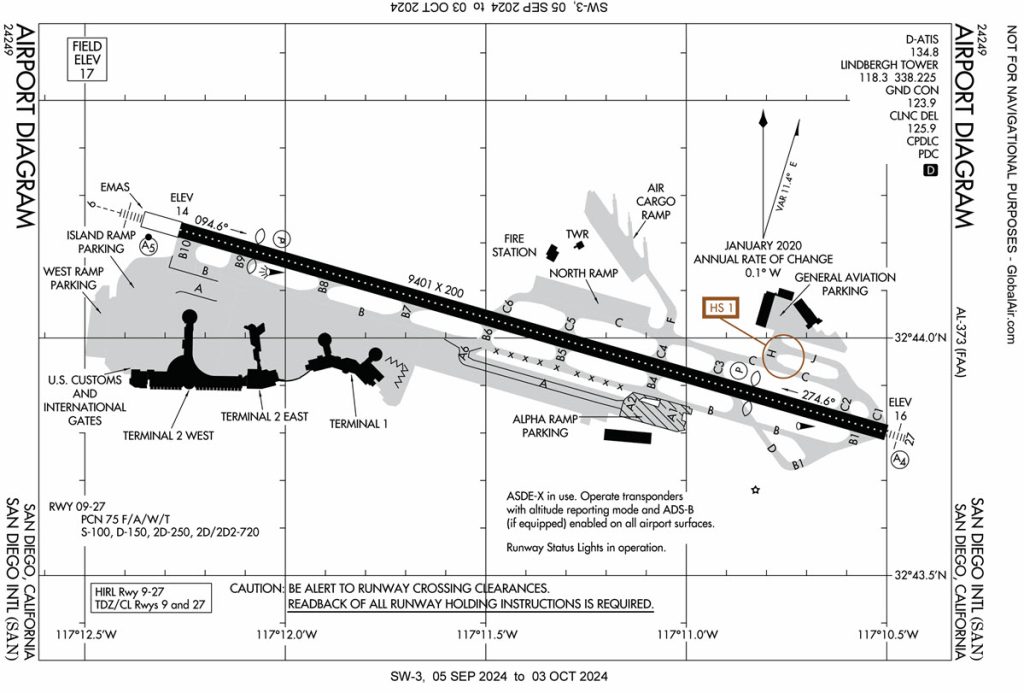

San Diego is a one runway airport with localizer only approach (in 2003) to the 9,401 foot long Runway 27 – the one we almost universally landed on. Due to a hill and a parking garage, Runway 27’s threshold is displaced 1,810 feet, leaving just 7,591 feet of useable runway for landing, a little short for a 757 but manageable. Most airline pilots will tell you that San Diego is a very challenging airport for landing. Added to that, there was a big red flag that I saw in my “What if?” mode, which was San Diego only has one runway. Where would I go if I couldn’t land there?

There was one airport that United served between San Diego and Los Angeles and that was Orange County’s Santa Ana, aka John Wayne. But that airport would be closed by a noise curfew by the time I got there during a divert. United didn’t serve Long Beach in those days, so LAX would be my only alternate if I could not land at San Diego. It was about 30 minutes flying time.

Having had LAX as a filed alternate on previous flights to San Diego, I knew the fuel burn for the 30-minute flight there was 3,500 lbs. The 757 has an average fuel consumption rate of 7,000 lbs. per hour (1,037 gallons per hour). Based on the one-hour fuel reserve my dispatcher had given me, if I could not land at San Diego and diverted to LAX, I would arrive there with just 30 minutes of fuel remaining. In the airline world, 30 minutes of fuel is a low fuel emergency.

Accepting my dispatcher’s fuel load meant I would be playing “I Hope Not” – as in if I could not land at San Diego, I would end up in a dire, low fuel emergency. I made a call to the dispatcher to request more fuel. At United, what the captain requested was the fuel he or she got. I asked him to give me a landing fuel of one and a half hours instead of the one hour on my flight plan.

He was miffed at my request and asked why I needed the extra fuel when what he gave me was more than legal. He then mentioned that the forecast was for clear skies and light winds and asked why in hell would I not be able to land there? I reminded him that San Diego is a one runway airport and that many things other than weather could close that runway and cause me to divert. Since SNA would be closed at that late hour, I would have to divert to LAX and arrive there with just 30 minutes fuel remaining, which would put me in a low fuel emergency.

He then asked how much fuel I needed and I told him to calculate a fuel load that would have me arriving at SAN with 11,000 lbs. of fuel, or a little over one and a half hours. I got the new fuel and an amended flight plan and took off for San Diego at 8 PM with an ETA of about 10 PM PST time.

“If” Happens

Upon my arrival in the San Diego area, the ATIS showed that a marine layer had moved over the field and the weather was now 1600 overcast with more than six miles visibility beneath the clouds. Runway 27 was the active and the localizer-only approach was advertised on the ATIS.

A marine layer is a typical phenomenon in the Southern California area due to the nearby Pacific Ocean. Under certain conditions, a layer of clouds would form over the ocean, then drift inland causing the forecast to be a bust.

While San Diego was still VFR, I would be flying above the clouds which would necessitate an instrument approach to get beneath the marine layer. Due to the hill and parking garage in close proximity to Runway 27, having a full ILS with a glideslope was out of the question. Also, in 2003, we did not have RNAV, so flying the localizer final approach course was the only option.

About 20 nm east of Runway 27, the approach controller instructed us to fly heading 240 to intercept the localizer and that we were cleared for the approach. A few minutes later, the localizer indicator started to move and we turned inbound flying at 5,000 feet.

About 10 miles from the final approach fix, and while level at 2,700 feet, we were instructed to contact the tower which we did and were cleared to land. Suddenly, a red slash mark appeared over the localizer symbol on our pilot flight display screens. This meant the localizer had just failed. I informed the tower of this and he asked our intentions. I asked how long before the localizer would be back in use and his reply was that they were working on it, and it would be back on in a few minutes.

We executed a missed approach and were instructed to turn right to a heading of 060 and to climb back to 5,000 feet. The use of maximum thrust while retracting the gear and flaps and climbing back to 5,000 feet consumed a lot of the extra fuel I had requested.

I talked it over with my first officer before deciding what to do. Should we divert now and land at LAX with an hour of fuel, or try another approach and hope the localizer would be back in operation? We agreed to try another approach based on the controller’s comment that it would only be a few minutes before it was back on the air.

We were vectored about 15 miles eastbound and parallel to the localizer Runway 27 course. A look down at my flight display screen. It showed the localizer icon still had a red slash through it. By this point, I had burned almost all the extra fuel I had put on and now a divert to LAX would put us in the low fuel emergency that I had tried so hard to avoid. What to do?

Out of desperation, I asked the SoCal approach controller to vector us onto a heading equivalent to the localizer course for Runway 27. This he did and we were soon flying heading 270 directly above what would have been the localizer course and started inbound to the airport in clear skies above the marine layer. I then asked him to descend us to his minimum vectoring altitude once we reached the final approach fix. He identified the FAF on his radar and cleared to descend to descend to 1400 feet.

During the descent, we broke out of the clouds and caught sight of the Runway 27 VASI, which we followed to a safe landing. Upon clearing the runway, I noted that our fuel remaining was 7,000 lbs., exactly one hour.

Get-There-Itis Almost Lured Me into Playing “I Hope Not”

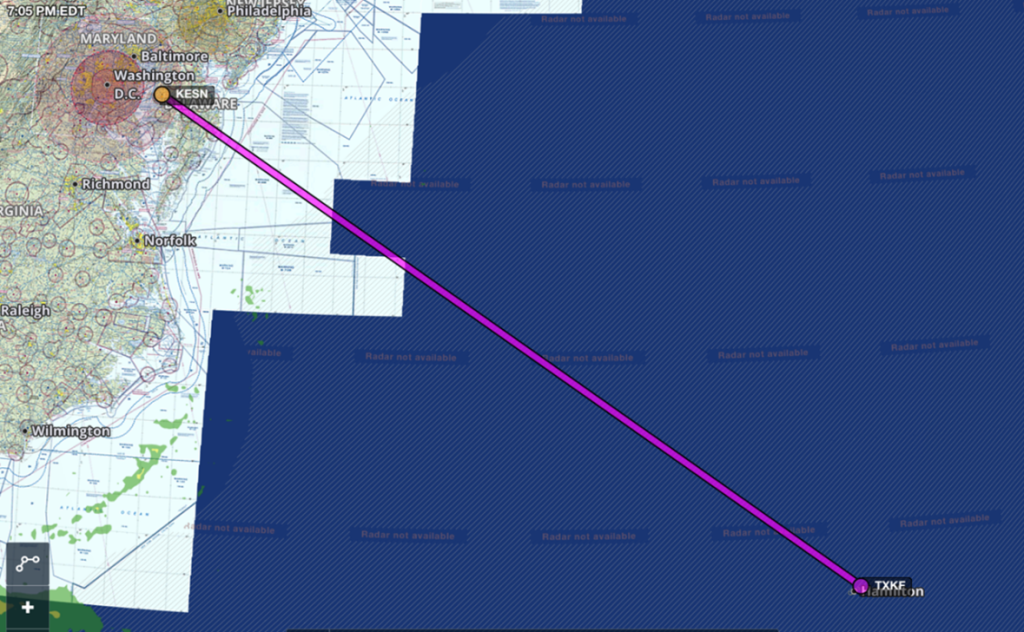

After my retirement from United Airlines in 2015 at age 65, I was hired to be the personal pilot for a wealthy family flying their single engine turboprop Pilatus PC-12NG. One day, during the summer of 2023, my boss asked me if we could fly the Pilatus to Bermuda for a week on the beach. That sounded like a dream come true, so I immediately started flight planning.

However, my initial flight planning found nothing but red flags. The first red flag was that the island of Bermuda is a tiny spec of land in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, all by itself. No other land masses were in close proximity to Bermuda. The second red flag was that its airport only had one runway which brought back memories of my ordeal at San Diego. I then did a weight and balance calculation and found that due to the five passengers and their bags for a week-long stay, I could not take off with a full six hours of fuel or I would be over the maximum gross weight of my Pilatus. This meant I could only carry enough fuel for five hours.

We would be departing from the Easton Maryland airport, KESN, since that is where I would pick up two of the five passengers before departing for Bermuda. The direct line distance from KESN to Bermuda was 677nm over water and would take 2 hours and 46 minutes. However, pilots on an IFR flight plan rarely get a direct routing. But even on a direct route, we would be landing in Bermuda with 2 hours and 14 minutes of fuel remaining which would normally be more than enough. In addition, the weather was forecast to be good VFR, which started to lure me into a sense of “Get-there-itis!”

But then I got into my “What if?” mindset with the “if ” being what if I couldn’t land in Bermuda? What would my alternate be? It didn’t take long to figure out that my only alternate was back on the East Coast of the United States, almost 650 nm away. In over 52 years of flying in the IFR system, I had never had an alternate while flying in general aviation this far from the intended destination.

And it was complicated by the fact that I would have to land at a legal port of entry, and not just the nearest airport available. Norfolk, Virginia was the nearest legal alternate I could find and it was 631 nm from Bermuda. Diverting to KORF would require 2 hours and 24 minutes flying time against the wind. Since I would arrive at Bermuda with 2 hours and 14 minutes of fuel remaining, and a divert would require 2 hours and 24 minutes, it hit me.

If I accepted the assignment, I would be playing “I Hope Not” – as in I hope nothing happens that would prevent us from landing in Bermuda, such as an aircraft accident, a disabled plane that closed the runway, or a thunderstorm that was not forecasted. If we couldn’t land, I would not have enough fuel to reach our alternate. This meant our only option would be to ditch in the Atlantic Ocean. With that thought, I politely told my boss we could not make the flight.

The One Runway Conundrum

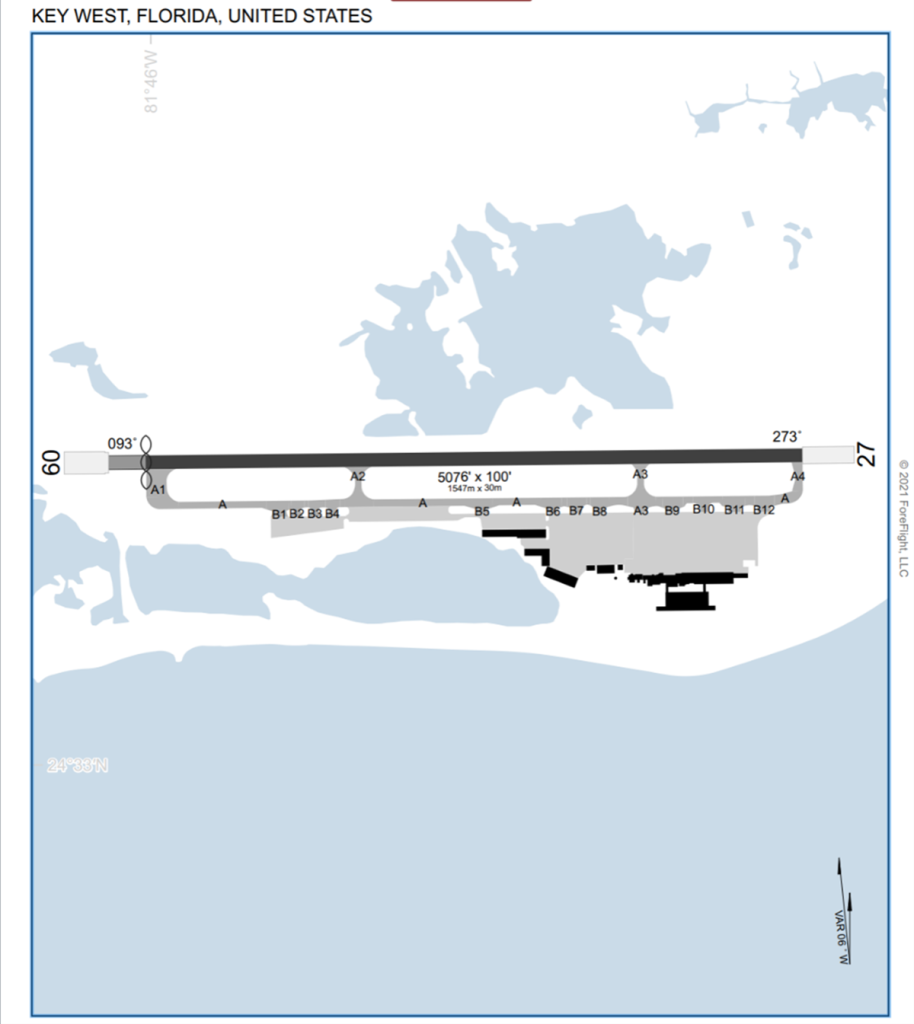

The Pilatus PC-12NG I fly professionally is based in Pennsylvania. My boss owns a vacation home on an island near Key West, Florida. Because of this, my normal flight route is the 1,120 nm flight between Pennsylvania and Key West. On southbound flights, after dropping my boss off at Key West, I would then fly the Pilatus solo up to Punta Gorda, Florida where I live and lay over at home until my boss needed me to fly him back to Pennsylvania.

The Key West airport has a single, very short runway 9/27 with heavy airline traffic. Due to close in obstacles, the threshold on Runway 9 is displaced 275 feet leaving just 4,801 feet for a Boeing 737 or Airbus A320 to land and stop. Those were the only airplanes the major airlines flew into Key West, with United being one of them. Having personally flown the 737 for some 10 years, I can say with authority that this is a very short runway for an airplane the size of a 737 or Airbus to land and stop!

Most airports with short runways and airline service have overruns off their departure ends that contain hundreds of brittle, hollow, concrete blocks known as EMAS. These blocks are designed to stop an airplane that runs off departure end of the runway by letting the airplane’s tires crush the blocks. This creates a huge amount of drag that quickly decelerates an errant airplane and hopefully prevents it from departing the airport property. The overruns of Runways 9 and 27 at Key West have about 300 feet of EMAS that extend from their departure ends to the airport boundary fence.

On one of my flights to Key West, I had dropped my boss and his family off and taxied out for takeoff on Runway 27. While I was holding for IFR release, I looked to my right and noticed that the EMAS for the departure end of Runway 9 was completely destroyed for its entire 300-foot length, with the destruction ending precisely at the fence that separates airport property from private property. This could only mean an airplane had failed to stop in the confines of Runway 9 and had experienced a runway excursion.

Based on the width of the tire tracks that had destroyed the EMAS, the airplane that could not stop had to have been a Boeing 737 or an Airbus A320. I pondered how many hours the Key West airport was closed while crews pulled a 120,000-pound airplane backwards through 300 feet of broken concrete blocks, and for the FAA to investigate the incident.

With one airplane stuck in the EMAS, there was no vacancy for a second one, which meant no other planes could land. Even though the sky was clear and visibility unlimited, the airport must have been closed for many hours to allow tugs to pull the plane out of the EMAS.

Conclusion

These stories should motivate pilots flying on long cross-country flights to airports with one runway to always play “What If?” instead of “I Hope Not,” regardless of the weather forecast. Playing “What If?” means having a plan B since, as mentioned above, many things besides weather can close an airport, causing “if” to happen.