By Joel A. Turpin, ATP CFII FAA Master Pilot

The most challenging, but enjoyable job I have had in over 59 years in the cockpit was as a commuter airline pilot with Skyway Airlines. The years 1973 to 1978 were spent flying a diverse fleet of airplanes, in some very diverse kinds of flying.

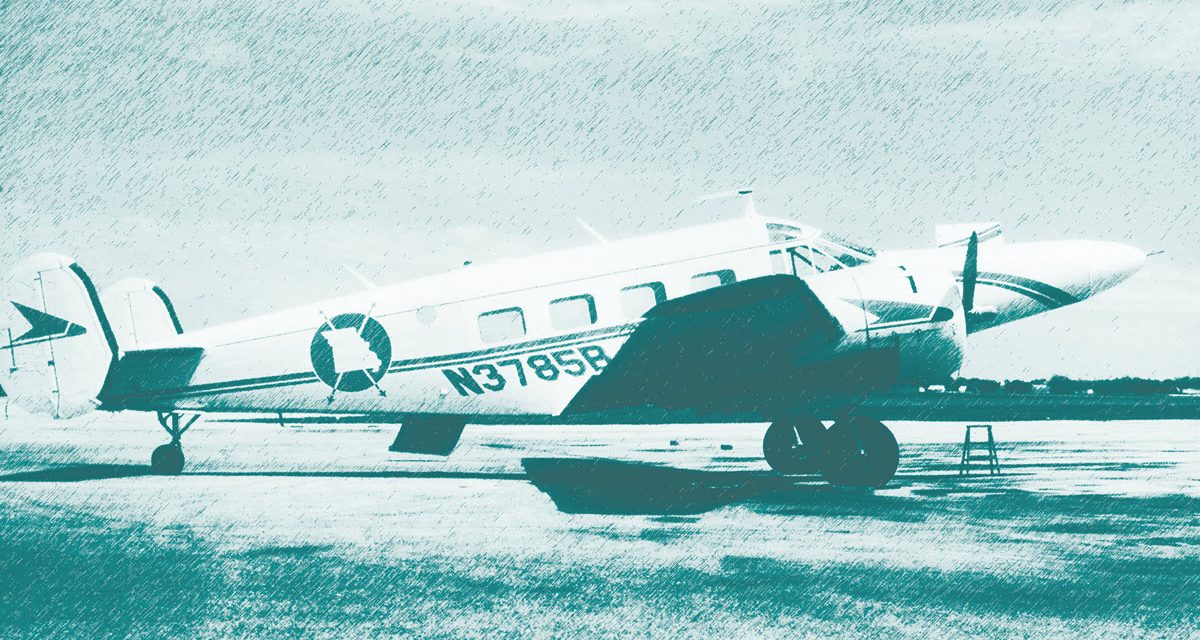

From our base at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, Skyway operated the tailwheel, radial engine Beech E18S, the turboprop Beech 99 Airliner, the DC-3, and four different types of single engine airplanes. We flew all of these planes in scheduled passenger operations throughout the state of Missouri. In addition, we flew prisoners for the military, passenger charter flights, freight, car parts, and contract mail at night for the US Post Office. Needless to say, flying for Skyway Airlines was both enjoyable and professionally challenging.

Another aspect of this job was the number of hours we flew. In the five years I was employed by Skyway, I flew over 5,000 hours, and sometimes as many as 135 hours in a month. Most of our pilots dreamed of flying the big jets for a major airline and needed experience. For a young pilot, there was no better place to hone one’s skills than Skyway Airlines!

My employment began on July 26, 1973, at age 23 right after graduation from college. Initially, I flew Piper Arrows, the PA-24 Comanche, and the Cherokee Six on our scheduled routes, as well as off-line charter flights. But within two weeks of my hire date, I was checked out as a copilot on the Beech 18 and the Beech 99.

One of the less fortunate aspects of flying for Skyway was the low and almost laughable wages we were paid. However, there was a silver lining to our pay scale. Low pay resulted in a steady turnover in our pilot staff, which in turn created many opportunities for advancement.

For example, from my initial flight as a Beech 18 copilot in August of 1973, I checked out as a Beech 18 Captain just seven months later. And by early 1976, I was Skyway’s Chief Pilot, training officer, and company check airman on all of our planes, except the DC-3. And by April of 1977, at age 27, I was a captain and check airman on our DC-3 as well.

Chief Pilot Duties

As Chief Pilot, my two main responsibilities were training our pilots and running the airline in a safe, legal, and professional manner. Other responsibilities included flying as a line pilot, test flying airplanes after heavy maintenance, and ferrying airplanes with mechanical problems to our maintenance base. As can be imagined, test flights and ferrying broken airplanes made for some very interesting flights!

Our maintenance facility was located at the Rolla National Airport (VIH), about 50 miles northeast of our main passenger base at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. Skyway had some top-notch mechanics working at this facility. However, since the company was eternally short of money, a mechanic’s ingenuity was often used as a substitute for new parts. A dearth of parts, a slim budget, and hard flying in old airplanes made for some exciting times for Skyway’s pilots.

Occasionally, one of our airplanes would arrive at an outlying station with a mechanical problem that precluded continuing the flight with passengers on board. If the airplane was still flyable, it would then be my job to ferry the ailing airplane to our maintenance base.

Sometimes the problem would be so serious the airplane could not even be flown on a ferry flight. In that case, a team of mechanics would be dispatched to the out-station in a truck loaded with their tools, and sometimes a spare engine. They would then complete the repairs on the ramp, regardless of the weather.

Changing an engine, or making other major repairs, out in the weather was definitely not the ideal situation. For this reason, we made every effort to fly airplanes with mechanical problems to our maintenance hangar.

As a line pilot, company check airman, flight instructor, and systems ground school instructor, I had become an expert with all of our airplanes. Because of this, my boss naturally expected me to use these skills to get airplanes with mechanical problems to the maintenance hangar and thus avoid fixes in the field. In this capacity, it was not unusual to ferry a Beech 18 with a cylinder out or other problems.

Because of my flight training, I was almost as comfortable flying the Beech 18 and Beech 99 on one engine, as on two. This comfort level was the result of the high turnover in our pilot staff which kept me constantly in instructor mode. As an instructor, I would routinely climb to a safe altitude and have the pilot I was training shut down an engine and feather the propeller. We would then fly around on one engine, accomplish all of the required training maneuvers, and conduct an air start. After more than a thousand hours of doing this, plus a few real engine failures, my confidence level was very high. I was especially confident in my ability to fly the Beech 18, my favorite airplane, on one engine.

This experience allowed me to make otherwise risky maintenance ferry flights with little danger or trepidation. However, none of the chances I took were careless or thoughtless. On each of my ferry flights, I religiously exercised what is known today as “risk management.” Using my systems knowledge, I would evaluate the maintenance problem, then calculate the risk involved in flying the airplane versus the benefits afforded by taking the risk. And, naturally, I always had an alternate course of action in mind if things fell apart during the flight. A perfect example of this occurred on August 10, 1976.

Ferry Flight Gone Wrong

The event actually began on August 9 when Captain Don Falenczykowski departed Fort Leonard Wood for the evening passenger flight to St. Louis. He was flying Beech E18S N5611D. After dropping off some passengers at the Rolla National Airport, Donny then departed for his next destination, St. Louis’ Lambert Field. About 40 miles southwest of St. Louis, Donny scanned the engine gauges and was shocked to see the oil temperature on the right engine running so hot it was almost pegged on the red line. He then checked the oil pressure. It was a bit low due to the oil temperature, but not critically low. His next move was to make certain the oil shutter was fully open, the oil shutoff valve was open, and the oil cooler bypass control knob was full down and directing oil to the oil cooler. Everything was in order which made the high oil temperature a mystery to Donny.

He quickly decided not to continue on to Lambert Field and told the approach controller he wanted to divert into the Spirit of St. Louis airport, which was less than 20 miles away and right along his course. Donny then throttled the right engine back to zero thrust and made an uneventful landing at Spirit. Another Skyway plane picked him up later that night and took him back to our home base at Fort Leonard Wood, leaving the Beech 18 parked on the ramp.

The next morning, I reported for work and was immediately summoned to the flight dispatcher’s office. Bob Williams, our dispatcher and director of operations, had a job for me. I was instructed to fly as a passenger on one of our scheduled flights to Rolla, where our Chief Mechanic would board the flight. The two of us would then be dropped off at the Spirit of St. Louis Airport to check on N5611D. If it was flyable, I was supposed to ferry it to our maintenance base.

Bob Rhodes was Skyway’s Chief Mechanic. Bob was young, handsome, and a hot shot maintenance technician. Bob and I were both in our late twenties and both in charge of our respective work groups. Bob supervised Skyway’s mechanics, while I was in charge of the pilots. We shared a great mutual respect as well as a good working relationship. We had also done a great deal of maintenance test flying together.

Upon our arrival at the Spirit of St. Louis Airport, we visually inspected N5611D but could find no obvious mechanical problems. Bob then pulled the oil screen, checking for metal, but it was clean. The oil level was at the normal 6 gallons and the oil cooler and ram air tunnel were clear of obstructions.

Next, we pulled the prop through by hand, but the engine turned over smoothly with no unusual noises. The final step was to start the engine and conduct a full run up. We agreed that if the engine checked out, we would take off and ferry the airplane the 100-statute-miles to the southwest, back to our maintenance base where it would receive a more thorough check. The weather was clear with just light winds and a temperature of 85 degrees, so weather would not be a factor.

We boarded the Beech 18 and, with me in the left seat and Bob in the copilot’s seat, started both engines. When the oil pressure and temperatures stabilized, I ran the engines up, cycled the propellers and checked the magnetos. With no apparent anomalies and all engine gauges parked comfortably in their respective green arcs, I looked at Bob and asked his opinion on flying the airplane. He said he thought it was safe to fly, and I agreed.

We taxied into position on Runway 25, planning a straight-out departure, which was the exact direction we needed to fly to the Rolla National Airport. I advanced the throttles toward takeoff power but made one change to the normal routine; I only used 25 inches of manifold pressure on the right engine while setting the full takeoff setting of 36.5 inches on the left engine. The takeoff roll, lift off, and initial climb out were uneventful. But just as we climbed through 1,500 feet, the right engine, without warning, shuddered, lost power, and literally destroyed itself internally.

With well-practiced hands, I quickly went through my 10-step memory checklist and had the right engine shut down, secured and its propeller feathered in less than 30 seconds. I trimmed for single engine flight and started a turn back towards the Spirit of St. Louis airport, but hesitated. We would now be faced with an engine change on the ramp, in the hot sun, 100 miles from home.

I looked over at Bob and asked if he would mind if we just continued on to our maintenance base. Bob quickly agreed to my suggestion, thrilled with the prospect of changing the engine in his hangar rather than on a sun-baked ramp. However, before committing us to the plan, my mind went into risk management mode. I had to balance the risk with the reward. Could we do this safely?

Close Call

The first consideration was that we had no passengers on board. We were also flying well under the maximum allowable gross weight and were operating under FAR Part 91. In addition, I had flown this same route a hundred times in single engine airplanes, which was what we were currently flying.

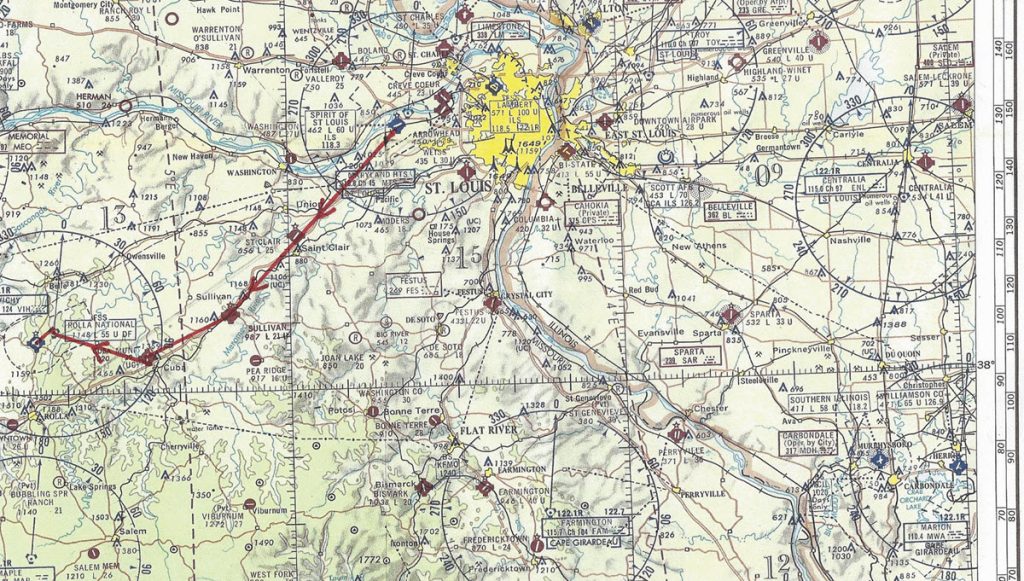

Then I thought of three airports spaced about 25 miles apart along the route that could be used for an emergency landing if the plan went awry. This meant there would always be an emergency landing field less than 15 miles away either ahead of us or behind us. Those three airports were the key to my decision to continue the flight on one engine back to our maintenance base.

It would be a calculated risk, but no more dangerous than if I were flying the same route in, for example, the single engine Cherokee Six.

Executing the plan, I altered my course from a direct line to the Rolla National Airport, to one that took us directly over each of the three airports along our route of flight. All three were situated right along Interstate 44. They were: St. Clair airport, the Sullivan Airport, and the then new airport at Cuba, Missouri.

I climbed to 3,000 feet, made a slight course change to the left and headed directly for St. Clair Airport, passing just south of the airport at Washington, Missouri, in the process. Leveling off at cruise altitude, I then reduced power on the left engine to 2100 rpm and set 30 inches of manifold pressure. This power setting gave us an adequate cruise speed while not putting any undue strain on our only remaining engine.

Executing the plan, I proceeded to fly directly over all three of my contingency fields and then, on the final leg, angled to the northwest and tracked inbound on the Vichy VOR, which was located about five miles northeast of our destination airport. The enroute portion of the flight to our maintenance base was accomplished according to plan without incident.

Five miles northeast of the Rolla National Airport, I contacted the Flight Service Station, located on the field, and found they were using Runway 22. I explained to the ATC Specialist that we had an engine shut down and declared an emergency. He said there was no reported traffic in the area.

But he was sitting in an office with a limited view of the airport traffic pattern. Since he didn’t have radar, “no reported traffic” only meant that no one had contacted him via radio on the common traffic frequency to report their position. Since this was an uncontrolled field, the use of radios was not required, but responsible pilots used them to report their location to other airplanes operating in the area.

The prolonged operation at a higher than normal power setting combined with a low cruise airspeed on a hot summer day had caused the left engine’s oil temperature to hover in the lower yellow arc. Noting the hot engine, I added one more item to my risk management plan. I now had to avoid, at all cost, a single engine go-around.

As I lined up for a straight in final approach to Runway 22, I began to think that the most challenging ferry flight I had ever made was about to come to a successful conclusion, and I felt good about it. However, that thought was premature.

I transmitted my position on the common traffic advisory frequency along with my intention to make a straight in approach to Runway 22. I also transmitted, in the blind, that we were an emergency aircraft flying with an engine shut down. Two miles out, I lowered the landing gear, set the flaps to the approach setting, and advanced the left prop control lever to high rpm.

At that point, the first indication of trouble appeared. I caught sight of a single engine airplane on a left down-wind leg for Runway 22. Mentally projecting our closure rate, I could easily see that we would both reach the runway threshold at the same time. I tried to contact the other airplane by radio, but its pilot did not respond.

As the distance between us shrank, I was finally able to make out the type of airplane in the traffic pattern. It was a Pitts Special, a modern, aerobatic biplane and it should have had at least one radio onboard. But for some reason, its pilot refused to acknowledge my continuous transmissions. I reduced airspeed to increase the interval between us and turned on my landing lights, hoping that this would draw his attention to my airplane. But when he turned onto base leg, it became obvious that the pilot of the hot little Pitts did not see me. He then turned onto final approach with me less than a mile behind.

A feeling of relief quickly replaced my fears when the Pitts’ pilot made a perfect landing in the touchdown zone. If he turned off the runway at the first available taxiway, the conflict would then be resolved. However, my feeling of relief quickly changed to chagrin when the Pitts’ pilot casually rolled past the first taxiway and trundled on down the runway at a leisurely pace.

As I crossed the runway threshold at 100 mph, the Pitts was still on the runway, not too far ahead. Things were happening fast and I had to make a decision. It looked like my worst fear, a single engine go-around, was about to become a reality.

At 20 feet above the runway, I initiated a go-around by advancing the left throttle to full power. But my airspeed was now down to 90 mph and the airplane abruptly rolled to the right. The abrupt roll when power was applied meant that I was now too slow for a single engine go-around. It was time for some more risk management.

Since going around was no longer an option, I had no choice but to land and deal with the possibility of colliding with the Pitts. But I did have an “out.” If needed, I could always steer my Beech 18 off into the grass alongside the runway and avoid a collision.

With the new plan decided upon, I quickly pulled the left throttle to idle and landed behind the Pitts Special. I braked hard as the distance between us rapidly shrank and finally brought the Beech 18 to a safe stop just as the Pitts’ pilot casually made a right turn onto Runway 31, the next to the last possible exit point. He had used nearly 5,000 feet of runway.

Final Words

Since a Beech 18 cannot be taxied on one engine, we sat parked in the middle of Runway 22 until a Skyway Airlines tug showed up and towed us to the hangar. Now that the emergency was over, anger began to well up inside. I kept an eye on the other pilot as he sauntered into the flight service station.

Once our mechanics had taken the wounded Beech 18 off my hands, I made a beeline to the FSS to confront the guy who had just put my life in danger. However, before heading for the FSS, I stopped to examine the Pitts Special. What I saw increased my anger to the danger level. I spied his instrument panel and noted that not only was there a VHF communications radio installed, there were two of them! In fact, there were enough radios and navigation equipment to make the Pitts legal for IFR flight.

As I entered the FSS, I came face to face with a man in his late forties with slightly graying hair. My first impression was that he was an airline pilot out flying his little toy on his day off. Trying hard to remain civil, I explained to him what had transpired and that he had cut an aircraft with an emergency out of the traffic pattern.

I also pointed out that his lack of diligence, and his failure to clear the runway in a timely manner had caused me to attempt an extremely risky single engine go-around. I then confronted him with the fact that his airplane was equipped with 2 VHF radios and asked why wasn’t he using them to communicate with me. But one look in his face told me that none of this information was of any consequence to him.

Deciding that his best defense was a good offense, he returned my vitriol in kind when he said “I had my radios turned off! This is an uncontrolled airport and for your information, mister, radios aren’t required at uncontrolled fields!”

Further conversation with the Pitts’ pilot, some of it heated, revealed that it was his personal policy to never use his radios when they weren’t absolutely required by FAA regulations. He claimed that to do otherwise was wearing them out unnecessarily.

His explanation for using almost the entire runway to stop revealed a similar philosophy on brake use. To save his brakes, he always coasted to a stop, trading runway for brake wear. I can only imagine how many other pilots had made go-arounds while he was saving his brakes!

He also stated that he had actually seen me on final approach but didn’t give way because I was not entering the traffic pattern in an approved manner. I explained to him that I had declared an emergency which gave me the right of way over all other airplanes, including him. He said “How would I know you had an emergency? I had my radios turned off!”

With that statement, I curled the fingers of my right hand into a fist and drew my arm back to throw a punch to a well deserving face. But before I threw that punch, I hesitated. Knowing that the next logical step in my interactions with this man would result in jail time and consequently the end of my dreams of becoming an airline pilot, I simply turned around and walked away.

ADDENDUM

The cause of the engine’s initial oil overheat and eventual failure was traced to an oil scavenge pump whose normal function is to return oil from the engine sump back to the oil tank. Its failure reduced the amount of oil the main pump could supply to the engine’s crankshaft bearings and other critical components, causing them to fail due to lack of lubrication.