By Carl Ziegler, A&P/IA

The sounds of summer: birds, kids in swimming pools, airplanes flying overhead, the happy banter you hear on the com, and the sound of your three-blade McCauley propeller ripping into your Powertow tug that you left on the nose gear of your Rockwell 114 Commander after you pulled it out of the hangar. Sigh!

I hope this doesn’t sound familiar, but events like this are not uncommon. I was recently reminded of a similar incident, where a new owner put gas in the airplane and then neglected to secure the fuel cap, which is located on top of the fuselage just below the pylon. You guessed right! After engine start, where did the fuel cap go? On a pusher-engined airplane, everything ahead of the engine is possible FOD (foreign object debris) for the poor propeller. The three-blade MT propeller, which is composite, lost an inch or two on each blade, as it chopped into the free-flying fuel cap. Until you see the damage that one bird can do on a fan or an airliner, it’s difficult to figure out how one item can do so much damage to so many blades! Now if that wasn’t bad enough, I received a text later that this owner apparently decided to fly the airplane to his home base with the three damaged propeller blades. I can only imagine the vibration of a 200-horse Lycoming sitting on a pylon spinning three damaged blades. Thankfully, he made it okay.

Here is the next $10,000 question: Will the aircraft owner have the required Lycoming airworthiness directive completed due to the prop strike or will he just go ahead and install a new MT propeller?

In this case, he did the right thing and complied with the AD.

Prop Strike Case Studies

In addition to occasional pilot-induced events, we have the gold standard of prop strikes: gear-up incidents. Given the frequency of gear-up accidents I’ve seen in reports over the last few decades, I’m not sure which one we’re going to run out of first: retractable-gear aircraft or propellers.

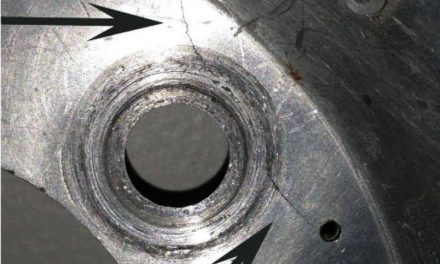

The Rockwell Commander 114 Powertow tug incident happened at my airport, and we were the ones to remove the now, highly-modified propeller. We took the engine off and up to our local rebuilder for a complete teardown inspection. Given the photo of the propeller (see picture above), you can see prudence was a better part of judgment on this one. I took the propeller off and was able to wiggle the blades in the hub. Just for fun I took the whole propeller apart to see what else was damaged — it was pretty impressive. There was no getting around this one. The damage required an extensive inspection and a hefty insurance bill.

Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

JOIN HERE

Still have questions? Contact us here.

Carl has close to 50 years of continuous experience working as an aircraft technician and 38 years as an IA. In addition to GA, he has acquired over 38 years of airline experience with Northwest and most recently with Delta, finishing his last 13 years of airline service as an aircraft inspector. He currently flies a 1976 Cessna 172N.