Vehicle reliability takes on a whole new level of importance when the vehicle in question shifts from a motorcycle, car, or truck to an airplane. After all, the normal consequence of an engine failure in a vehicle confined to land is that it rolls to a stop and you have to call the auto club.

A pilot’s problems are only beginning when the engine fails, and the consequences of mismanaging the emergency landing can be considerably more severe.

For that reason, engine reliability is one of the primary concerns of many aviators. TBO can be a major consideration when operating an aircraft, but an equally important measure of an engine’s ability to continue running in adverse conditions is how many times it has to visit the shop between overhauIs.

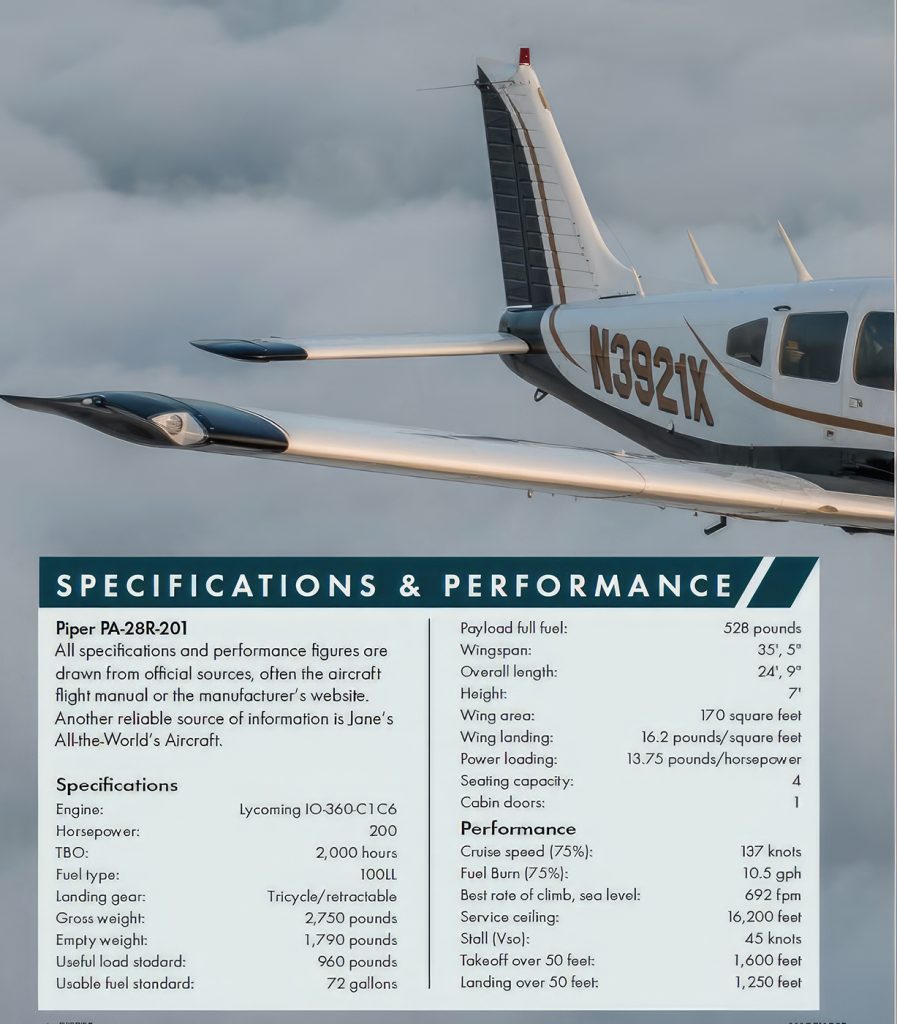

The Lycoming O-320 and O-360 series engines are almost universally regarded as perhaps the most bulletproof of powerplants. They’re essentially the same engine bored out an additional 40 cubic inches. The O-320 (carbureted, horizontally opposed, four cylinder) was the standard engine installed on all the entry-level, four-seat Pipers, and the O-360 and IO-360 (same engine with fuel injection) were employed on the Piper Arrow.

Lycoming’s little IO-360, developing either 180 or 200 hp, was the engine of choice for the Arrow, and it was an excellent engine indeed. The early Arrows, 1967 through 1969, were virtual copies of the Archer from the underwing up. The Archer was a popular fixed-gear airplane that was created to appeal to pilots seeking a little more power than the Cherokee 140/Warrior. The initial retractable Arrow used the 180-hp engine, and the 200-hp version became standard equipment in late 1969.

Time between overhauls (TBO) was set at 2,000 hours, and that number was actually attainable, unlike the optimistic estimates placed on some other aircraft engines. If operated regularly in moderately dry climates, run consistently and serviced with new oil every 25 hours, many IO-360s in non-commercial, Part 91 operation lasted far past the published time between overhauls, some as long as 2,500 hours. When there was a problem, it was usually nothing worse than sticking valves, though even that could sometimes ruin your day.

Piper also experimented with the IO-720 engine on the Comanche 400 — essentially a pair of IO-360s welded together end-to-end to produce a single, behemoth, horizontally opposed, eight-cylinder, 400-hp monster. Remember that avgas in the mid-1960s was about $1 per gallon, so the 20-22 gph fuel burn wasn’t as intimidating as it would be today. Though the basic engine was reasonably reliable, hot start irregularities and other problems with magnetos, starters, etc., doomed the model to a short two-year run.

The IO-360 in the 200-hp version of the Arrow enjoyed a specific fuel consumption of about .40 pounds per horsepower per hour, so a typical 75% cruise setting resulted in a theoretical fuel consumption of 10 gph. By the time theory met reality, that number was closer to 10.8 or 11 gph, which is still reasonable economy.

The engine wasn’t the only feature of the Arrow that smacked of reliability and supreme functionality. Like the fixed-gear Cherokees before it, the Arrow featured Johnson bar manual flaps that clicked through three deployed settings, along with full up. This allowed extending or stowing flaps in a second or two, which was a mixed blessing as the flaps were so powerful, they could overcontrol the pitch attitude if you became too enthusiastic.

At least the mechanism was perhaps the most reliable possible method of extending and retracting the flaps, not to mention the fastest. Later Arrows switched to electric flaps that worked slower and were more efficient, but far less fun.

The Arrow also sported a durable and effective suspension system. Oleo struts all around gave the Arrow a reasonably smooth ride on rough surfaces, unlike the Arrow’s chief competitor, the Mooney Executive, that used rubber “doughnut” suspension on the main gear. This imparted a rougher transition across bumps in the taxiway, though neither airplane was appropriate for off-airport operations.

Arrows, from the very beginning (1967) used an all-flying, stabilator tail design rather than a conventional control and made the airplane more responsive at low speeds and high angles of attack.

Roll rate was appropriately slow, considering that the airplane was at least partially targeted for pilots stepping up from lesser-powered, fixed-gear Cherokees who were seeking a high-performance endorsement. Many new pilots liked the airplane’s roll and pitch response. Some even judged it as marginally quicker than the Mooneys, though the Mooney was by far the fastest of all the 200-hp retractables.

The wing on the Arrow started off as a standard, fat, Piper airfoil, a creation of Fred Thorp and John Weick. The airfoil featured a section known for extremely docile stall characteristics and almost totally benign handling. In 1977, Piper adapted the semi-tapered Warrior wing to the Arrow, allegedly conferring an improved roll rate and slightly less drag. The better control response was barely apparent, but by any measure, the new wing was an aesthetic success.

As if all that wasn’t enough, the original Arrow’s premier attraction was something no one else in the industry had, at least, not at first. The PA-28R-180 flew above an automatic gear extension system. (Both Bellanca and Beech copied the feature and offered their own systems.) This was basically an aneroid device that sensed when the airplane’s speed dipped below 80 knots and would lower the wheels automatically Since the Arrow’s fat wing made it nearly impossible to land at 80 knots, this feature made gear-up landings next to impossible without pilot interference.

In theory, this protected the Arrow from pilots who forgot to extend the gear, but some aviators still managed to find a way to land the airplane on its belly. The automatic extension system was almost bound to work too well and sure enough, it did exactly that.

There was a cut-out lever that allowed a sales rep to sidestep the auto-extend feature to demonstrate a short field, obstacle takeoff, or a go-around. In keeping with Murphy’s Law, some salesman forgot the cut-out, ignored the flashing light and warning horn, and landed with wheels firmly tucked in the underbelly.

In another instance, an Arrow pilot lost power within easy glide distance of an airport. The pilot slowed the airplane to glide speed, unfortunately, a speed below the auto gear system’s threshold. The auto extension system obediently deployed the wheels, adding drag. Now, there was no way to get the wheels back up because the engine was dead and no longer providing hydraulic power. The Arrow landed short and was severely damaged, though no one was hurt.

Following the inevitable litigation that aircraft manufacturers never expect to win, Piper reasoned that no good deed goes unpunished, and the cure might be worse than the disease. (One more — no one learns anything from the second kick of a mule.) The company discontinued all future installations of the Arrow’s innovative automatic gear extension system.

Despite the fact that both the Arrow and Mooney 201 used the same engine and horsepower, the Arrow couldn’t come close to the Mooney’s performance. The 201 climbed better, was at least 10-15 knots faster and had a higher service ceiling, but none of that seemed to matter as the Arrow quickly closed the sales gap with the Mooney and stepped out in front as the world’s most popular retractable.

The Piper Arrow survived, while Mooney phased out its 200 hp model in 1997. The Arrow is still regarded as the least expensive 200-hp, high-performance retractable on the market, though its future is uncertain.

Since the Arrow’s fat wing made it nearly impossible to land at 80 knots, this feature made gear-up landings next to impossible without pilot interference.

In theory, this protected the Arrow from pilots who forgot to extend the gear, but some aviators still managed to find a way to land the airplane on its belly. The automatic extension system was almost bound to work too well and sure enough, it did exactly that.

There was a cut-out lever that allowed a sales rep to sidestep the auto-extend feature to demonstrate a short field, obstacle takeoff, or a go-around. In keeping with Murphy’s Law, some salesman forgot the cut-out, ignored the flashing light and warning horn, and landed with wheels firmly tucked in the underbelly.

In another instance, an Arrow pilot lost power within easy glide distance of an airport. The pilot slowed the airplane to glide speed, unfortunately, a speed below the auto gear system’s threshold. The auto extension system obediently deployed the wheels, adding drag. Now, there was no way to get the wheels back up because the engine was dead and no longer providing hydraulic power. The Arrow landed short and was severely damaged, though no one was hurt.

Following the inevitable litigation that aircraft manufacturers never expect to win, Piper reasoned that no good deed goes unpunished, and the cure might be worse than the disease. (One more — no one learns anything from the second kick of a mule.) The company discontinued all future installations of the Arrow’s innovative automatic gear extension system.

Despite the fact that both the Arrow and Mooney 201 used the same engine and horsepower, the Arrow couldn’t come close to the Mooney’s performance. The 201 climbed better, was at least 10-15 knots faster and had a higher service ceiling, but none of that seemed to matter as the Arrow quickly closed the sales gap with the Mooney and stepped out in front as the world’s most popular retractable.

The Piper Arrow survived, while Mooney phased out its 200 hp model in 1997. The Arrow is still regarded as the least expensive 200-hp, high-performance retractable on the market, though its future is uncertain.

Of course, the Arrow’s primary claim to fame is that it’s an amazingly easy airplane to fly. Full flap stall speed is only 45 knots, so you needn’t feel out of your depth flying approaches at 65 knots. The flare is so easily predictable and the payoff so incredibly gentle that practically anyone can feel confident about landings after only a few hours in an Arrow.

If you’re interested in acquiring an Arrow, there are a veritable plethora (is there any other kind?) of airplanes available, dating from the original 1967, 180 hp models with the old Hershey bar wing to the latest 200 hp airplanes with the semi-tapered wing. Along the way, there was a turbocharged model, along with a T-tailed version that many at Piper thought was stylish. Unfortunately, it didn’t sell well and was discontinued after a few years.

Whichever model you choose, you’ll be selecting one of the most reliable retractables on the market, an airplane that can transport you from where you are to where you need to be in reasonable time with excellent safety.