By Laurie Einstein Koszuta

Top it off.” Three simple words, but three of the most dangerous words in aviation. Three words that could kill you, any passengers on board, and innocent people on the ground. You’ve probably even said those words to a line service technician (LST) on the ramp. When you say “top it off” to the LST standing ready to fill your tanks, you’re flirting with disaster. Sound overly dramatic?

“Absolutely not,” said Keith Clark, Senior Quality Control and Technical Representative for Phillips 66 Aviation. “When pilots use those words, a misfueling event could be in the works.”

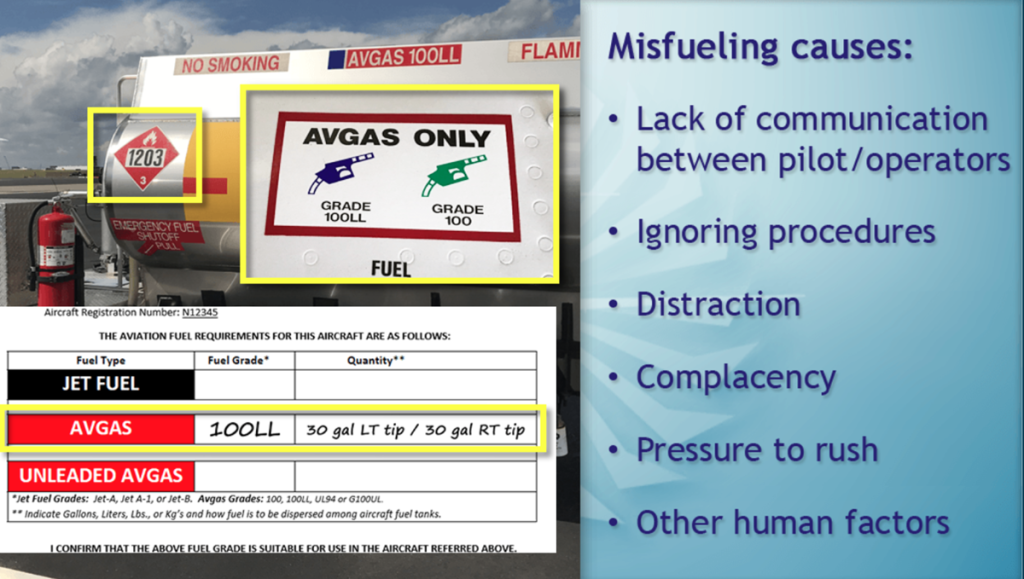

According to Steve Berry, Managing Director of Safety and Training with NATA (National Air Transportation Association), misfueling occurs anytime the wrong grade, quantity, or fuel type is pumped into an aircraft. For example, a misfueling occurs when Jet A is pumped into a tank that requires avgas or vice versa. It is also a misfueling event when fuel is pumped into the wrong tank or the wrong plane.

Photos courtesy of Steve Berry.

Provide the Necessary Details to Eliminate Guesswork

“Misfueling is preventable,” Clark said, “because simply asking for a ‘top off’ doesn’t give the LST enough information to know exactly which fuel to use, how many gallons are requested, and which tanks should be filled. And, if the LST gets distracted or there is a time lapse between the ‘top it off’ order and the actual fueling, he may not remember the plane’s tail number. Pilots cannot assume that every LST at every airport is available immediately, can read their minds, or is familiar with every aircraft they service. The truth is that no pilot should ever expect or assume that.”

Clark noted that LSTs may fuel 20 or more aircraft daily at airports. Some take jet fuel, others avgas. In 10 days, that accounts for more than 200 aircraft; in 100 days, the number climbs to 2,000. “In basketball, a 90% free throw average is exemplary,” Clark said, “but nothing short of 100% in aviation fueling is acceptable. Every fueling has to be perfect, or a tragedy could occur.”

The consequences of introducing jet fuel into an aircraft designed to run on 100LL (100 low lead octane) avgas are devastating. Jet A is refined kerosene. At high power, reciprocating piston engines can’t withstand the extreme temperatures of jet fuel as it burns. As the cylinders in the engine detonate, performance is immediately compromised, resulting in complete failure. The pilot has minimal control or time before a forced landing becomes inevitable.

Both Clark and Berry said that pilots continue to believe the myth that an aircraft misfueled with Jet A instead of avgas won’t even start, much less be able to taxi, complete a runup, or take off. This skewed thinking, they said, offers a false sense of security. Planes can appear to run normally since the fuel lines may still contain just enough avgas to function before the jet fuel reaches the engine and detonation begins. The reverse, in which avgas is used to fuel a jet turbine engine, can also cause failure, but the deterioration in performance is variable.

Even if the aircraft never leaves the ground and the error is discovered, introducing the wrong fuel can mean a lengthy and costly maintenance process requiring an authorized mechanic to drain, flush the tank, and inspect the engine for possible contaminants or damage. It could also mean a total replacement if the engine is damaged beyond repair. “In that situation,” Clark said, “at least a catastrophe was averted, and the pilot and passengers are alive.”

Clark also pointed out that with some pilots converting old piston-driven engines to diesel compression, those engines now require Jet A instead of avgas. “If avgas is put into those engines, that plane is coming out of the sky. You cannot assume that an LST will know about possible modifications that have been made to your airplane.”

“Complacency among pilots continues to be a huge issue,” Clark warned, “and many believe that misfueling could not happen to them. Too many pilots have relied on the notion that Jet A nozzles won’t fit into an avgas tank because of its larger duckbill design. However, it has been proven repeatedly that the nozzle’s size or opening doesn’t matter. Some inexperienced LSTs have difficulties and inadvertently try to circumvent the opening and fill the tank with the wrong fuel.”

Misfueling Can Happen to Even the Most Experienced Pilots

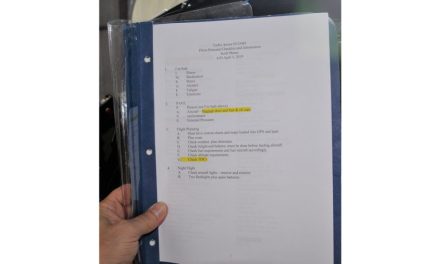

The late Bob Hoover, the renowned “pilot’s pilot” whose extreme attention to detail and vast experience during World War II were legendary, also suffered the consequences of a misfueling after the war. In 1978, after the airshow aviator had performed in his P-51 and Rockwell 500S Shrike Commander, he asked that his Shrike Commander be fueled with 60 gallons of 100LL avgas. Usually, Hoover stood by while his aircraft was fueled, but on this occasion, he got distracted or was delayed in the airport manager’s office. As he and his passengers entered the piston-powered plane, he was unaware that the tanks were full of jet fuel.

After climbout to about 300 feet, the engines failed, even though the gauges on the instrument panel appeared normal. As the plane rapidly lost altitude, Hoover managed to crash land into a deep ravine, causing severe damage to the aircraft but saving everyone on board. How could this have happened to an experienced aviator? Could sumping the fuel before the flight have prevented this accident?

“Even if Hoover had sumped the fuel before the flight, it wouldn’t have mattered,” Clark said, “Sumping is not an indicator that everything is okay. Mixing 100LL avgas and Jet A will yield the blue color pilots are used to seeing. Not only that, the fuels will not separate. It is also possible that the distinctive kerosene odor of jet fuel may not be noticeable if the two fuels are combined.”

In a 2015 accident, a Cessna 421B pilot, with impressive type ratings for single, multi-engine, and instrument, experienced almost immediate dual-engine failure after his plane reached 2,100 feet. The pilot could maneuver the aircraft enough to make a forced, hard-impact landing on a Texas highway. He was seriously injured, and his two passengers sustained minor injuries. The crash site reeked of jet fuel. Investigators later learned that 53 gallons of jet fuel had been pumped into the tanks instead of avgas. The pilot had sumped the fuel on preflight, and as expected, the sample was the light blue tint he recognized as avgas. The pilot’s most significant error? He was absent during fueling and didn’t communicate or verify the fuel type needed in his tanks.

Unfortunately, not all pilots walk away. In 2019, a former pilot examiner perished in Kokomo, Indiana, after a misfueling caused the 1981 Piper Aerostar 602P he was flying to crash. The LST who fueled the airplane told investigators that the pilot requested a top-off. Unfortunately, the LST mistakenly believed the plane was a jet and filled it with Jet A. The pilot signed the receipt, which clearly denoted Jet A, and paid for the fuel without noticing a discrepancy in fuel type. It was a tragedy that could have been averted.

Industry Safeguards to Avoid Misfueling

Over time, the aviation industry has developed process improvements and additional safeguards to prevent misfueling. Using color-coded handles (black for jet fuel and red for 100LL avgas) attached to fuel hoses has helped. So has the application of sizeable color-coded identification placards and decals prominently affixed to refueling trucks. However, even with such interventions, there have been reports of fuel trucks outfitted with the wrong nozzles or nozzles that were interchanged and swapped between trucks.

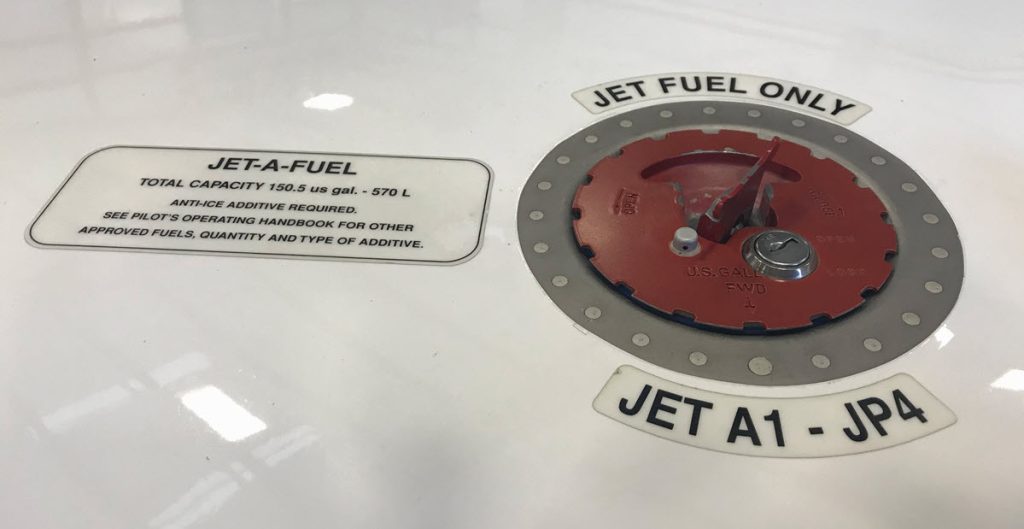

Even the fuel placards on aircraft have issues. At EAA AirVenture 2023, Clark randomly surveyed 20 planes parked in two rows on the grass. He found that nearly half were missing wing placards or had placards that were illegible. How would any pilot expect an LST to know what grade of fuel those aircraft required without the placards present or visible?

Every pilot should be aware that their pilot operating handbook (POH) states the specific requirements for placards on the aircraft. FAA regulations also require them. 14 CFR Part 23, Sec. 23.1557 — Miscellaneous markings and placards states, “Fuel filler openings must be marked at or near the filler cover….” and then lists the requirements for the different types of engines. Without the placards, the aircraft is considered unairworthy.

One crucial safety change came from airplane manufacturers who followed the suggestion to remove the word “turbo” from the side of turbocharged planes, as it would be possible for inexperienced LSTs to think that “turbo” and “turbine” are the same type of engine.

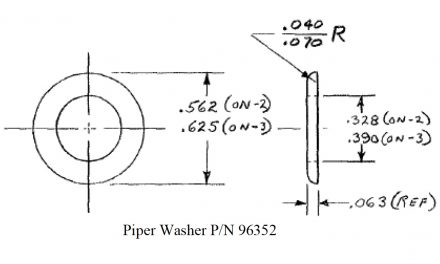

The industry has also recommended the installation of adapter rings to reduce the possibility of introducing jet or turbine engine fuel nozzles into the filler openings of aircraft requiring avgas. Unfortunately, even with such a safeguard, there have been too many occasions when the wrong fuel was forced into the tank.

All of these precautions make a big difference, but they’re not exhaustive or foolproof. “Those things are beneficial,” Clark said, “but the solution is that the pilot communicates the fuel type, grade, and quantity to the LST every time a plane is fueled. It is critical.”

Save a Life — Verify Fuel Type

Clark speaks passionately to thousands of pilots yearly at aviation events like AirVenture and Sun ’n Fun about this subject. “I just cannot emphasize the danger of misfueling enough,” he said. “I want to help save lives. That’s why I developed the ‘Save a Life — Verify Fuel Type’ safety initiative. The goal is to help pilots learn from past mistakes and provide education and prevention through communication and verification.

The program has been adopted and incorporated into the training that NATA offers its members and promotes heavily on the website preventmisfueling.com. The program’s signature logo features a bright red, heart-shaped logo with the words “Save a Life — Verify Fuel Type” on placards and decals that can be attached to fuel trucks, fueling mats, credit card machines, FBO windows, and aircraft.

“If there’s that red heart-shaped logo on fuel trucks,” Clark said, “it will help remind the pilots and LSTs to clearly communicate and verify the fuel.”

Clark also pointed out that flight instructors must discuss this subject with their students so they hear and understand the dangers of misfueling. Their life and the life of their passengers depend on it.

And, what about aircraft of the same type and color parked side-by-side on the ramp? It does happen. What if instructions are given to an LST to fuel the Piper Navajo they see outside the FBO? “We have seen situations,” Clark said, “where the LST didn’t even notice that there were two Navajos beside each other and filled the wrong plane and didn’t fuel the plane that had requested fueling. What happens to the pilot who thinks his tanks are full when he’s ready to take off? These situations could be avoided by having the pilot give a complete fuel order to the LST, verifying the tail number, the fuel grade, how the fuel should be distributed to each tank, and then double-checking the receipt before signing it.”

Inattention to such details and pilot carelessness are topics that Clark repeats often. He relates the story of a pilot who, upon landing a Cessna 421, asked for jet fuel, thinking it was the King Air he routinely flew. Fortunately, the LST knew the difference between the two aircraft and immediately pointed it out to the pilot, thus averting a tragedy.

The bottom line, Clark emphasized, is that the pilot is in charge of the aircraft. The LST is not flying the plane. Relying on others to know what to do because they work in an airport or fuel planes daily is a deadly assumption.

“During safety training about Save a Life,” Berry added, “we don’t discuss specific aircraft types because it doesn’t matter. What matters is that the placards on each aircraft match the placards on refueling equipment. If a pilot is taxiing and radios to the FBO that he needs refueling, the pilot must indicate his tail number so the LST can match the tail number to the request for fuel. It’s the only unique information that identifies every aircraft and avoids mistakes.”

In 1993, Transport Canada developed a concept they called the “Dirty Dozen.” The idea was to find common denominators or pre-cursers that could impact the outcome of a flight. It was a way to understand the causal effect of human error in aviation accidents. Many human factors were compiled, with the dozen comprising the most common. They include lack of communication, complacency, distraction, stress, pressure, lack of awareness, norms, fatigue, lack of teamwork, lack of assertiveness, lack of knowledge, and lack of resources. All of these factors can affect both pilot and LST.

Berry said every general aviation pilot must apply a consistent standard when ordering fuel regardless of the reason they fly, whether for recreation, agriculture, or business. Saying “Top it off” isn’t an adequate standard. Communicating a proper fuel order — including grade, type, and tail number, and verifying everything, including looking at the receipt for the proper fuel type before you sign — is the standard because it’s the most accurate way to prevent tragedy in the air.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Free Decals

“Save a Life — Verify Fuel Type” decals are available from Phillips 66 Aviation at no charge. Email trustedfuel@p66.com with the quantity requested and include shipping address and phone number.

Videos

These two short videos provide more information about misfueling.

- Aviation Week Network Video Learning Session 23 Seconds Can Make a Difference. The link to this 26-minute YouTube video, hosted by Keith Clark, can be found on the landing page of preventmisfueling.com.

- Phillips 66 Presents: Save a Life – Preventing Aircraft Misfuelings. Google this title to access this 14-minute YouTube video presented by Keith Clark.