The owner of a Piper Archer noticed that fuel was leaking from his carburetor under certain conditions. The members of the Piper Owner Society then discussed if there could be any valid reason for that. Here are the top tips on Piper carb leaking from that discussion.

Should a Piper engine carburetor ever leak?

Question

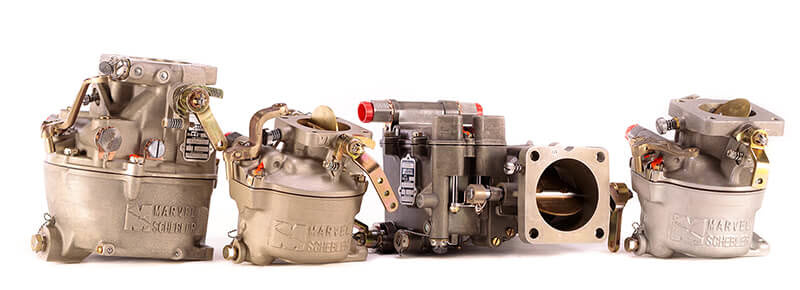

I am a new owner and a student. I found another squawk on my plane. Engine off, I advance mixture lever to rich or turn on the electric fuel pump, and fuel starts dripping out of the throttle bore, past the carb heat damper, and into the bottom cowl. Is this typical of old Marvel-Schebler 0-360 carbs? Could this be a bad float bowl valve or fuel jet? The engine runs great in flight. I’m wondering if this affects the mixture and fuel efficiency in flight.

It’s definitely not normal, but I’ve read about this condition in other forums about other planes, as well. I have trouble understanding how an assembly that really doesn’t have much stress or rotational wear on its parts can lose tolerance enough to leak fuel and require a rebuild. These aren’t auto carbs that are being opened and closed constantly.

We see some fuel drippage the day after flying after putting the plane away for the night. So that setting would be mixture at full lean, throttle full idle, pump off. We think that as we taxi back to the hangar at three-quarters rich and then shut off, there is some fuel that leaks out of the carb. Maybe engine heat expands the fuel in the bowl, but more times than not, after flying there are blue streaks on the white nose-wheel pant. But more shocking is just pushing the mixture up or turning on the electric pump when engine is cold, we get fuel drips.

— Yellowtail

Answer #1

Our “updraft” carburetors are mounted below the engine and rely on engine vacuum to draw the air/fuel mixture into the intake. Fuel should never leak out of a carb unless something is wrong or if someone pumps the throttle while the engine is stopped.

When the throttle is pushed forward, the accelerator pump squirts fuel into the carb throat. If the engine is stopped, there’s no vacuum to draw the fuel into the engine and the fuel drains out (as mandated by gravity). If another attempt is made to start the engine and it backfires, or if there is a spark source nearby (like an alternator, starter, or bad plug wire), that fuel can ignite.

The procedure for a carb fire is to stop screaming, crank the starter, and attempt to draw the fire back into the carb. If that doesn’t work, evacuate everyone from the plane, get your fire extinguisher out, and put out the fire. If that doesn’t work, call the fire department and your insurance adjuster, because you’ll probably need to file a claim. After exhausting all these steps, it is perfectly acceptable to scream.

Here’s the bottom line: If the engine is not turning, it doesn’t matter where the mixture control is, whether the electric fuel pump is on or off, or the position of the fuel selector. Nothing should be leaking fuel, especially the carburetor. It sounds to me like a float, needle valve/seat, or gasket issue. If anything on your plane is leaking fuel, it’s telling you something is wrong.

Please let us know what you and your A&P/IA find.

— Jim “Griff” Griffin

Answer #2

It’s true that (airplane carbs aren’t) opened and closed as much as an automobile. We don’t stop for cross traffic and we can’t pull over to the nearest cloud when we have a flat tire or run out of gas!

What we do have is an engine that is rather large for the horsepower it makes and has a very large rotating mass that is somewhat balanced — when all the parts were new. I say somewhat balanced because even though the prop is statically balanced when new, I don’t think all the other parts firmly attached to the rotating mass are balanced. Plus, when assembled, all the parts have a small looseness-of-fit that allows them to be assembled to their mating parts by hand without needing a press to force them together.

This looseness, or tolerance, between all the parts allows them to be assembled very slightly off from their individual centers of gravity, creating an out-of-balance condition. Then, with time and an A&P’s file, the prop is forced to become imbalanced, out of necessity.

The prop, because of its relatively large size, can become very unbalanced by small amounts of weight being taken off out near the tips, where most of the sand and rocks make their little stress-riser nicks, which the A&P has to dress out. Yes, they usually try to dress all blades equally, but I have yet to see an A&P show up to work on my airplane with an NIST calibration certificate tied around his neck.

I say all of this because it is probably the vibration that, over millions of cycles, beats the moving parts and pieces into submission. Given enough time, with its increasing intensity, this vibration will increase the wear and tear on everything on the airplane.

Everything attached to the engine takes the most beating from vibration. Think about your exhaust system, with those long pipes being constantly shaken until they crack, releasing that sneaky and deadly carbon monoxide. More isolated from the vibrations but still affected are those very expensive instruments in your panel. Even the pilot and passengers are affected.

Three weeks ago, a friend and I dynamically balanced our props. My airplane is remarkably smoother. My friend’s RV-10, which was not as out of balance as my Archer, was also remarkably smoother. His wife, who has over 1,200 hours as a passenger, said he should have had this done years ago. She was never so happy about his monetary expenditure on an airplane.

— Ray

Conclusion: I researched prop balancing and that is now on my refurb list. We removed the carb today and noticed a little leakage out the throat when I pushed the mixture level to full rich, so the plane is going to the shop for new internals this week.

— Sid

Aircraft Carburetors 101: Click Here.

Join in the discussion here in the Piper Owner Society forum.