World’s Smallest Four-Seater

For as long as there have been little airplanes, the gold standard has been those that can carry up to four people. Notice the use of the term “can.” We’re not talking four full-size humans here. Not even three 170 pounders, just four souls, at least two of whom will need to be downsized.

Two-seaters certainly have their uses. A half century ago — or was it a full century, time blurs reality — my first airplane was a two-place Globe Swift that featured room for a smallish pair of people. Airplanes that carry a deuce can make relatively inexpensive trainers, reasonable traveling machines for two folks, and wonderful Sunday go-to burger transports, but for those pilots who occasionally have a need for four seats, they’re obviously two buckets short.

Like many general aviation pilots, the latest of my subsequent airplanes usually hauls around two unused seats. I plead guilty to almost never using the rear seats for real live humans.

Yes, I am aware that I’m paying to carry around the larger engine, bigger wing, and stretched fuselage required to accommodate four humans. My airplane’s fuel burn is higher than it needs to be to haul two folks and my insurance premium also suffers because of my preference for a four-seater that has carried four people perhaps a dozen times in the last half-century.

I learned to fly in a two-seater — a ragged little J-3 Cub at Merrill Field up in Anchorage, Alaska, more years ago than I can remember — so perhaps I’m entitled to fly with just my wife and an occasional Siberian husky in back. The impromptu Cub certainly seemed big enough for me and my quasi-instructor way back when. Floyd was a burly prison guard in the real world with nothing more than a private certificate and a quirky Cub called, all-too appropriately, Slow Poke. Floyd was a good guy and an enthusiastic instructor — without a rating. He never did acquire the proper credentials. He never saw the need for any more than two seats, and back in those early days (ages 13- 15), neither did I.

My happy little Globe Swift was a fun, sporty machine that looked like a miniature fighter. Unfortunately, it had systems designed by a lawn mower mechanic and an instrument panel like something out of a South American locomotive.

All my subsequent airplanes have seated quartets, at least theoretically. Trouble is, four-seat airplanes by definition need extra weight, wing, and horsepower to get the job done. Or do they?

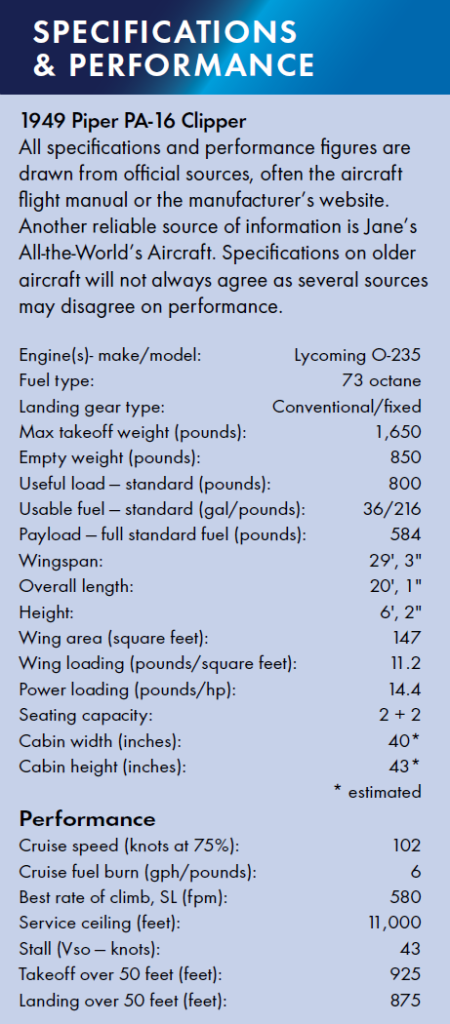

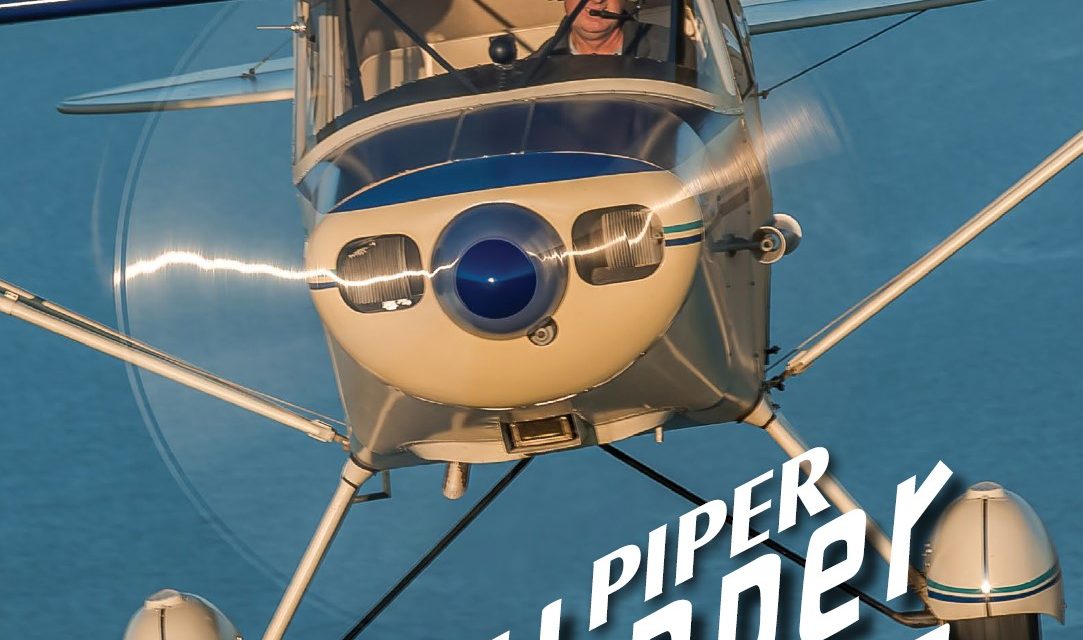

Piper built a model in the late ’40s that could carry four folks (or so they say) on a far less grand scale. The fabric-covered Piper Clipper made do with a comparatively tiny Lycoming O-235 engine rated for only 115 hp; yet the PA-16 still managed to offer four seats. Admittedly, creature comforts weren’t much on that ’40s-vintage model. The aft creatures had to be very small indeed. But still, there were four seats installed. Sort of.

The PA-16 Clipper was produced only in 1949, an extended fuselage version of the earlier Piper PA-15 Vagabond, yet another attempt to milk the basic J-3 Cub airframe and wing for all it was worth, and it was worth a lot. The Vagabond fattened up the Cub fuselage to accommodate two folks mounted side-by-side rather than in tandem. Then, the Clipper stretched the cabin to make room for the extra seats in the miniscule aft compartment.

Piper built 736 Clippers in 1949, before bowing to Pan American Airlines’ claim that they owned the name Clipper and that Piper should cease and desist. Since Pan American had more lawyers than Piper, the little Lock Haven-based company changed the Clipper’s name to Pacer in 1950 and again upgraded the airplane, stepping up from the Lycoming O-235 to an O-290, first rated for 125 hp, then 135 hp. The Pacer also offered an extra door, more fuel, and more modern yokes in place of the Clipper’s joystick control for roll and pitch.

Personally, conventional sticks have always seemed more fun and convenient than yokes. They don’t block or inhibit access to any control or switch, they take up less space and they’re typically installed in a location that’s not used for any other purpose. Sadly, none of the current crop of Pipers offers stick control.

As the specs suggest, the Clipper grossed only 1,650 pounds and, in an ideal world, had a typical empty weight of 850-900 pounds. Today, more than a half-century later, in keeping with Murphy’s law of weight gain with age (which applies equally to airplanes and people), the same airplane might weigh in even heavier. If you assume the 900-pound empty weight and a full 216-pound fuel load, you’d be left with 534 pounds of payload for people and stuff. That’s hardly four human’s worth, but even dedicated owners agree that the airplane wasn’t a real four-seater anyway.

Takeoff was a fairly casual affair. Basically, you pushed power up and waited for the little four-cylinder Lycoming to gather itself for the effort to fly. Under the best of conditions, the Clipper lifted off in less than 1,000 feet, started uphill at about 580 fpm at sea level, and the service ceiling was a not-very-reassuring 11,000 feet. A good cruise height was 3,000 to 6,000 feet MSL. That meant the PA- 16 probably wasn’t a good candidate for operation out of Denver on a hot summer day, at least not with a full load.

Despite this, the Clipper was an agile little devil, with wide-span ailerons that extended along two-thirds of the trailing edge of the wing. Accordingly, roll rate was fairly quick in contrast to the Cub. Pitch response was also good, the fastest of the three control axes.

Perhaps by some fortunate mystery, the Clipper manifested less adverse yaw than the J-3. Rudder coordination was still mandatory in turns, and adverse yaw forced you to lead turns with rudder rather than aileron, but foot application was less than you might have expected considering the airplane’s vintage and heritage.

Level at 6,500 feet where 75% power was all there was, the Clipper managed to trip along just over 100 knots under ideal conditions. The 36-gallon fuel supply allowed cross-country flights of about 5 hours plus reserve, so hardy souls could plan on spanning almost 500 miles between fuel stops.

Stalls were typical Piper, and if you practiced at altitude, they were so slow that the airplane seemed almost to be hovering in place. There was nothing sinister about the Clipper’s stall characteristics. If the rudder was coordinated and the ball was in the center, the Clipper broke straight ahead, with little tendency to drop a wing or roll off into a spin.

During actual transitions from sky to ground, the Clipper didn’t fit the image of the squirrelly little taildragger, but it was short coupled. It was a reasonable three-point airplane, and if you held it off long enough, the Clipper would eventually plunk down at about 43 knots in a full stall. Many pilots prefer to plant the PA-16 onto the mains in what came to be called a “wheel landing.” In either case, the Clipper was a respectable short-field machine, easily adaptable to operate in and out of unobstructed 1,000-foot strips and not too picky about the runway surface. The Clipper had few habits that could lead an unwary pilot astray. I’m fairly wary flying other people’s airplanes, and I’ve been led astray in other tailwheel machines, but never by a Clipper.

The Clipper/Pacer was one of the first airplanes on which Piper chose to move the third wheel up under the nose to create a tricycle-gear machine, this one called the Tri-Pacer. Again, some pilots hailed the first tricycle-gear Piper as a modern innovation, while other more cynical aviators labeled it as more of a bastard child of “what used to be a pretty good airplane.”

Depending upon who’s asking and who’s answering, the Clipper was either a delightful addition to the short company from bankruptcy by the quickest, most economical means possible. It’s not certain which role was recognized as dominant, but the Clipper did make a valuable contribution to Piper’s tailwheel legacy.

Clippers sold for less than $3,000 during their one year of production, a pretty minimal tab for an alleged four-seat airplane. Most Clipper owners laugh at the mere suggestion of carrying four full-sized folks and regard three as a maximum load, or perhaps two adults and two kids.

And yet, the Clipper somehow manages to retain its own badge of honor. It was one of the last of the Piper taildraggers that hung their collective hat on the Cub (except for the Super Cub itself, of course, a design that was to remain in production for almost 40 years). The Clipper had a larger cabin, and logic suggests it could have served many of the same bush pilot applications as the Super Cub if fitted with the same 150-hp engine.

Today, original Clippers are rare — especially beautifully restored examples. A recent look through the pages of Trade-A-Plane (before the print magazine ceased production) revealed only three Clippers for sale at prices ranging from $25,000 to $30,000. All three had been upgraded in horsepower, two to the 150-hp Lycoming O-320 and the third to a slightly less enthusiastic 135-hp Lycoming, and it’s likely those examples truly might be capable of lifting four folks and transporting them across near horizons.

Despite its horsepower limitations, the Clipper did offer a side-by-side alternative to the Cub, and the back seat could accommodate enough baggage to allow owners to journey far from home, something you’d definitely be challenged to accomplish in a Cub.