When do I need an engine teardown?

Recently, I had a call from a customer. In this case, the customer had an issue with a propeller. The customer’s aircraft was parked and not moving, and a Cessna aircraft passed by too close. The high wing impacted the top end of the vertical blade on his three-blade propeller. No real visible damage. The engine wasn’t running, and the other pilot had insurance to take care of any damage.

This seemed like a very simple claim. But it has turned out to be a bit more complicated than we expected. But before I get into that, let’s talk about claims and propellers. If you happen to be the unfortunate person to have a propeller damaged, what can you expect your aviation insurance company to do?

Should I Submit a Prop Strike Claim?

Should you submit an insurance claim for a prop strike? Well, it depends. There are a number of variables that can affect the claims department’s decision. Some of those would be the kind of damage, the severity of the damage, the age and the hours on the propeller, and the propeller and engine factory guidelines. My disclaimer: I’m just sharing my experience. I’m not a mechanic, and I don’t work for the FAA. So, talk to your mechanic and/or the FAA before you do anything.

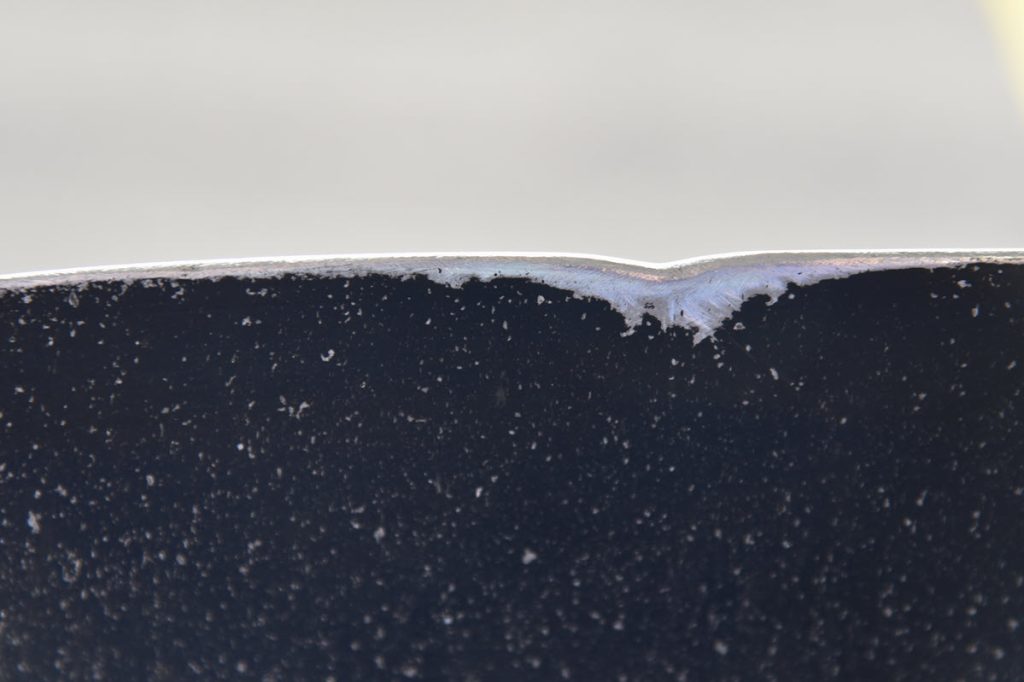

Let’s start with the minor nicks. Often, a propeller is damaged by debris or rocks on the runways, causing nicks and scratches. If you fly off grass or gravel, expect them. Don’t worry; many of these small nicks can be removed or filed out by the mechanic. But be careful with this. Through the years I have seen many propellers “repaired,” yet end up being damaged beyond repair.

Years ago, I had a friend who bought an aircraft that had a propeller that was filed below minimums. When the mechanic at the next annual (my friend’s first annual) tried to check a nick, it was below allowable minimums. That meant a new propeller and an unexpected expense! It’s very difficult to determine if you have a propeller that’s within limits when you purchase an aircraft. Few people give it much thought, especially when dealing with a fixed-pitch prop. I doubt most pre-buy inspections would have found the prop issue.

It’s a little easier with a constant-speed propeller. Buying or owning an aircraft with a constant-speed propeller usually means having the prop overhauled or maintained throughout its life. This means more attention is paid to the constant-speed propeller compared to a fixed-pitch propeller. Additionally, ADs that come out on the propellers have put emphasis on checking their condition.

If your prop has minor nicks and chips, the mechanic will likely try to fix the problem, and the cost will be below the deductible of the policy. If the nick creates enough damage to the blade that it needs to be replaced or needs a new prop, I think I would contact the claims department about filing a claim. This doesn’t mean they’ll do anything, but if the nick is substantial and needs to have the prop replaced, you could have a claim.

Typically, this type of damage — especially if it’s a big nick — would warrant some concern about the engine and the integrity of the prop. But nothing really needs to be done unless the FAA or manufacturer guidelines warrant it. Don’t jump the gun and contact claims and try to get a new prop. Remember, most small nicks and repairs won’t pass the deductible in cost, and if you file a claim, you now have a claim history and probably a premium increase at renewal.

Sudden Stoppage

We’ve all seen pictures of props with “Q-tips,” the bends or curls at the tips that prevent usage. A rule of thumb I have heard is that if the propeller is evenly bent on all blades, there is less chance of crankshaft damage. But, in my thinking, if the prop hit the ground and the engine stopped, I want a mechanic to check it. Call me a coward, but I would expect no less than a dial indicator on the crank flange. Dial indicators will probably be the first thing that a claims department will request. If there’s nothing out of round, they might just repair or replace the prop, depending on the manufacturer guidelines.

The insurance company doesn’t want to send the pilot out with a propeller and engine that might fail and cause a bigger claim, so don’t worry about being at risk because the company is cheap. If the blade damage warrants it, the claims adjuster will request that the engine be torn down and inspected for damage. But it goes further than just the claims adjuster.

I Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Teardown!

Many engine manufacturers require that the engine be torn down for any impact to a propeller. I have been told a few different things. One is that if the propeller needs to be removed from the engine to be repaired, the engine needs to be torn down. I have also heard that if the engine wasn’t turning, it doesn’t need to be torn down. What’s the correct answer? The engine manufacturer will be the best source.

A good example is the Lycoming Service Bulletin No. 533C, which describes when the Lycoming engine should be torn down for inspections from a prop strike and what they consider a prop strike. Part of the Service Bulletin is below.

Service Bulletin No. 533C (Supersedes Service Bulletin No. 533B)

SUBJECT: Recommended Action for Sudden Engine Stoppage, Propeller/Rotor Strike or Loss of Propeller/Rotor Blade or Tip

MODELS AFFECTED: All Lycoming reciprocating aircraft engines

This Service Bulletin identifies propeller/rotor damage conditions and gives corrective action recommendations for aircraft engines that have had propeller/rotor damage as well as any of the following:

- Separation of the propeller/rotor blade from the hub

- Loss of a propeller or rotor blade tip

- Sudden stoppage

A propeller strike includes:

- Any incident, whether or not the engine is operating, where repair of the propeller is necessary

- Any incident during engine operation where the propeller had impact on a solid object. This incident includes propeller strikes against the ground. Although the propeller can continue to turn, damage to the engine can occur, possible with progression to engine failure

- Sudden RPM drop on impact to wat, tall grass, or similar yielding medium where propeller damage does not usually occur

To read the complete 553C service bulletin and download a PDF click here.

In the case of my customer’s aircraft, his propeller was dinged by another aircraft’s wing. His engine wasn’t running, the other plane didn’t hit it at high speed, and there was no real visible damage. The complications came from the fact that the insurance company claims department wanted to tear the engine down for the inspection, but the mechanic and the owner didn’t think it was necessary in this situation. The claims department noted that the Lycoming service bulletin also included the following:

“A propeller strike can occur at taxi speeds and during touch-and-go operations with propeller tip ground contact. In addition, propeller strikes also include situations where an aircraft is stationary and a landing gear collapse occurs, causing one or more blades to be bent, or where a hangar door (or other object) hits the propeller blade. These instances are cases of sudden engine stoppage because of potentially severe side loading on the crankshaft propeller flange, front bearing, and seal.”

This description of the “prop strike” pretty much includes any kind of impact. The comment of “hangar door or other object,” seems to be inclusive and warrant the engine needs to be torn down for an inspection.

On a side note, this particular Lycoming engine had been modified for an experimental aircraft and did not have the Lycoming data plate installed anymore. It has a custom engine data plate instead, which opens up another whole set of questions as to what’s required, since it’s no longer a “certified” Lycoming engine.

My take on this situation is to take the side of caution. Even if it isn’t required because it is experimental, wouldn’t you still want it done? What makes the engine different when it comes to precautionary teardown? Just the data plate? If the engine was modified by porting and polishing and whatever else the custom company does, is it really a different engine inside? If it still uses the same crankshaft, connecting rods etc., wouldn’t the risk of damage still be there?

Who Pays for the Teardown?

Most companies will pay for the teardown and repair or replacement of the damaged part. Remember a small point here. An insurance policy is only required to return the aircraft to the condition that it was in before the damage occurred. What does that mean in a prop strike? If the crank was damaged, the insurance company does not have to buy you a new crank, especially if the crank was past TBO (Time Between Overhauls) or worn out.

Another factor would be any ADs that require replacement of parts. An example would be if you have an aircraft that is affected by the VAR/Airmelt crankshaft controversy. If I’m correct, the AD requires that if you open the case, the crank must be replaced. In the case of the teardown, if the crank is not damaged, you will have to pay for the new style crank. If the crank was damaged, the insurance company should pay for it. But again, it depends on the AD and the condition of the parts.

Don’t go into this with the grandiose idea of getting an overhaul for the cost of the prop … it doesn’t work that way. But I have not had any companies deny the repairs of the damaged parts, or the cost of the teardown or reassembly. Everyone that we have worked with has been very helpful. Disputes started when the insured felt that his aircraft engine, which was 200 hours over TBO, should be replaced. That is not, in my opinion, reasonable to expect from the insurance.

One positive example was the owner of a Cessna 210 that had a nose gear collapse on his aircraft. The engine was at TBO and the propeller damaged. The insurance company paid for the teardown and the reassembly. The owner decided to have the engine overhauled at this time and paid for the additional labor and the additional parts. He got a cheaper overhaul and the insurance company covered, indirectly, part of the cost.

This thought can be of concern if you have an aircraft needing repair. You might get your engine disassembled and find that there are a few things that need repair (rings, camshaft, cylinders, etc.), things that will not be covered by insurance because of normal wear and tear. This could increase the cost of your repairs, but don’t blame the insurance company. They haven’t been flying your aircraft and putting on hours. That’s your cost of ownership. The unexpected damage from an accident is the insurance company’s responsibility.