By Irven F. Palmer, Jr.

Have you looked at your propeller lately? I mean, have you really examined it and run your fingers along the leading edge during your preflight to detect any nicks or dings? Considering a new prop can cost over $10,000, we need to take care of what we have.

I flew in the Alaskan bush for more than 35 years. I realized early on that whenever I was flying to some off-airport location, my propeller was going to take a beating. That’s because whenever you operate from river gravel, a sand bar, or an ocean beach, you are placing your propeller in a highly abrasive environment.

The low-pressure area in front of the propeller, which is generated by the spinning prop, literally sucks up sand and small pebbles into the prop blades. The most critical time for propeller-blade abrasion is during the runup and takeoff, when ground speed is slow. As your ground speed increases, you start moving away from the particles of sand and pebbles and leave them behind.

I flew Piper and Cessna taildraggers. For off-airport operations, I found that conventionally geared airplanes were best, owing to the nose’s high position and greater prop-to-ground clearance. In addition, I used larger tires, giving me even more prop clearance. Those big tires, however, degrade airspeed, so that is a trade-off. Even with these advantages, a propeller is still going to suffer some erosion by the sand and gravel sucked up into it.

How does the prop pick up sand?

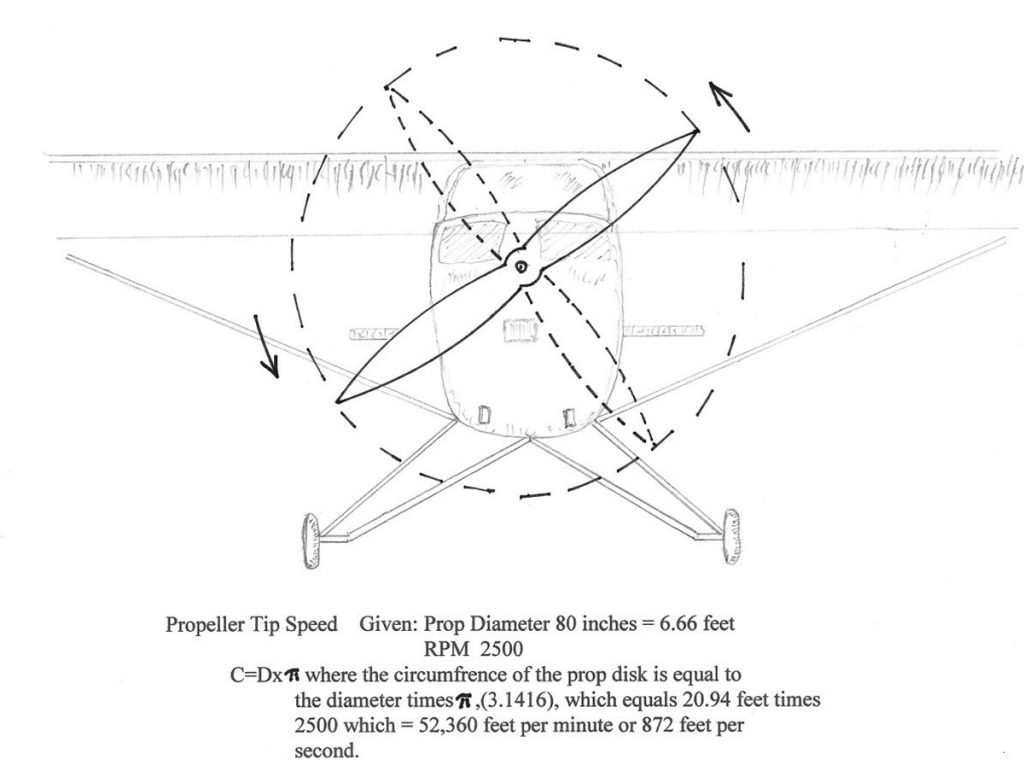

Let’s examine why the propeller sucks up the sand and pebbles. We will keep the math simple and not deal with angular velocity in radians. We will just examine the linear velocity, or tip speed, of the prop.

We all know the twist angle of a propeller blade varies from the hub to the tip. This angle, or pitch, as it’s called, is greater at the hub, the point of least velocity, and is gradually diminished toward the high-speed tips. It is the outer half of most propellers that do the most work. This twisted airfoil, which has the thickest material near the hub and thinnest material at the tips, allows the thrust load to be evenly distributed over the whole blade area. Sometimes called an airscrew, the propeller-blade tips travel through the air in a curve called a helix, which is somewhat in the shape of a huge screw-thread curve. And these tips move at an incredible speed.

Keep in mind that the rear of the prop blades is nearly flat and that the forward portion of the blades is curved and shaped like an airfoil. Imagine two small wings operating in the vertical plane. The lift, instead of being exerted in a vertical plane, is exerted horizontally, and we call it thrust.

Using my airplane as an example, let’s examine how fast the tips are moving to generate thrust and low pressure to suck up that sand. The sketch included here shows that the prop tips are moving at 872 fps or 600 mph. That is fast, and the little airfoil tips are creating a low-pressure suction that grabs all those sand grains and small pebbles and pulls them into your prop.

What techniques can I use to protect my prop?

If you operate on hard-surface runways from airport to airport, you probably will not have much prop abrasion. However, if you live in a windy area, you can be sure that sand will be blown onto the paved surface, and it will cause some abrasion to your prop.

If you have your own private airstrip that is not turf, or you operate out in the boondocks, there are some things you can do to minimize propeller abrasion, nicks, and dings.

When I lived in Alaska and used a river’s gravel bar for an airstrip, I threw grass seed into the rocks in the areas where I tied down, started the engine, and started the takeoff roll. In the cold Alaskan climate, a subspecies of red fescue grass works best. It germinates quickly and only grows to about one foot if left uncut. In the lower-48 temperate zones, fescue or other species can be used. At first glance, you might wonder, “How could those seeds take hold down there in the cracks and crevasses?” Well, they do. It’s like putting netting down on the rocks, and the little rootlets grab hold of all those sand grains and pebbles and keep them out of your propeller. I knew some folks, using very large, low-pressure tires, who flew out of airstrips that had cobble and boulder-size rocks. They thought, at first, that the grass seed would not take hold, but it did. It latches onto the sand grains down in those cracks and keeps that sand from coming up and sandblasting the prop.

If you fly to a lot of off-airport sites, you can’t possibly plant grass seed everywhere. So, there are some other techniques to use. Some folks take a big canvas and, using spikes, fasten it to the ground in the engine run-up area to protect the prop. Consider putting larger tires on your airplane to gain more prop clearance. One thing that is easy to do, and will help a little, is to apply a good coat of wax to the prop blades periodically to absorb some of the sandblasting. If you have a choice of take-off areas, pick a grassy spot rather than a sandy or rocky one. Also, if you are camped out someplace in the boonies, the best time to take off is when the sand grains are wet, like after the early morning dew or rain, as the moisture will stick the sand grains and pebbles together, helping to prevent them from being sucked up.

How do I perform an emergency repair in the field?

Major repairs to a propeller must be done by a certified propeller shop. Minor repairs can be done by your A&P mechanic. A propeller, spinning at such a high rate of speed, is subjected to tremendous structural forces and vibration. Any sharp nick or dent provides a focus for the stress to build up. Engineers have several terms to describe these focal stress points, but we can just think of them as points of possible fracture. Propellers do fracture and break on occasion. So, if you pick up a rock out there. Have your A&P look at your propeller when you get home.

Your engine may have a lot of horsepower, but it is your propeller that allows you to use it and get home. Have fun and be safe out there.