By Erich Rempert, A&P Consultant

Virtually everyone has seen “unapproved wiring” in a GA airplane. Can you think of an example? Can you think of an example in your airplane? Many of you will answer yes, and that’s not surprising in this age of iPads, portable GPSs, traffic systems, ADS-B receivers, intercoms, and aging aircraft.

Just as many of you will likely also think: “So what’s the big deal, it’s not permanent so it’s legal.” Well, maybe it is, and sometimes it really isn’t, but almost always it’s a bigger risk than you may imagine.

There are really two main types of unapproved wiring:

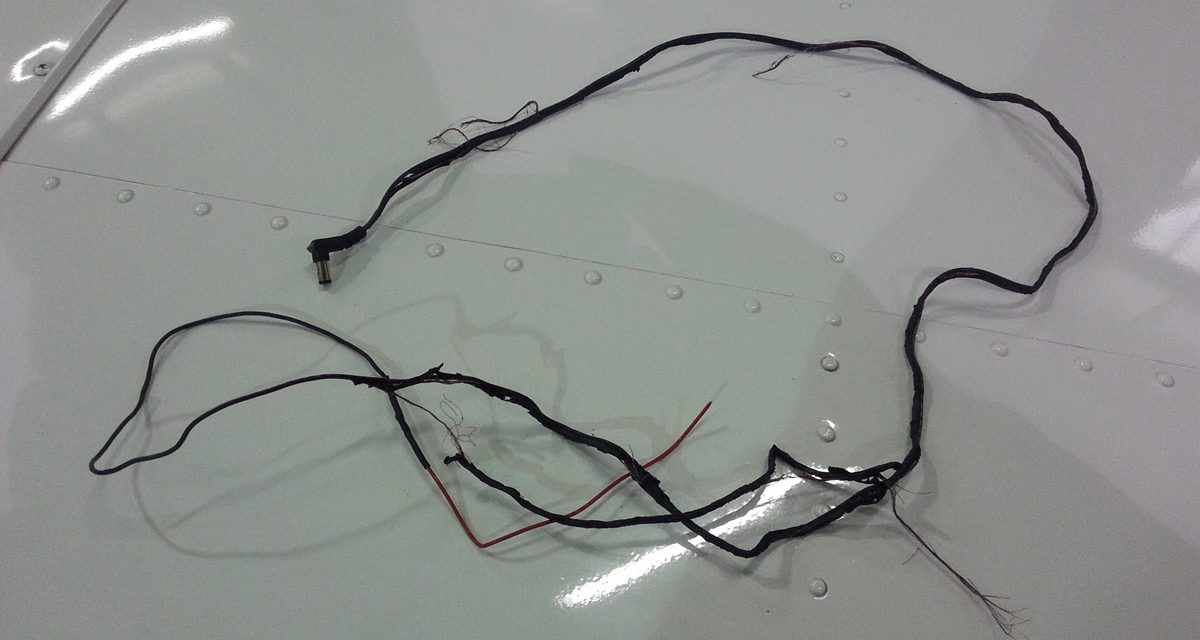

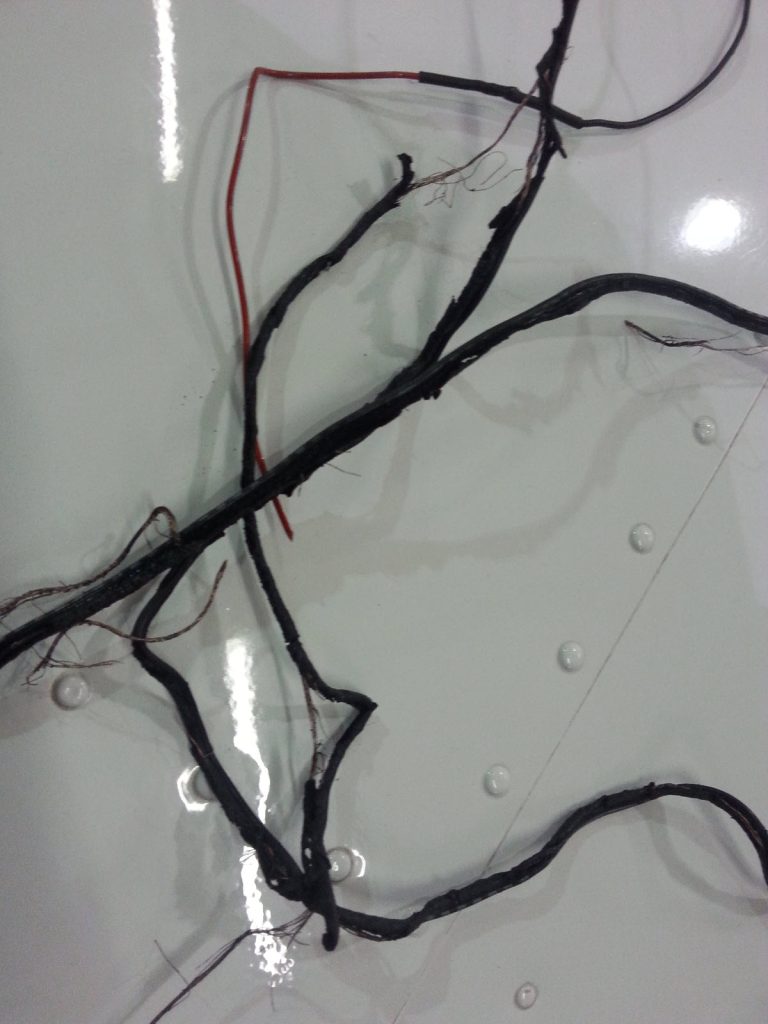

- Actual wire and wire components that aren’t approved or don’t meet industry standards; and

- Electrical circuits that have been installed in a manner that isn’t approved or consistent with acceptable methods.

Unapproved Wire and Wire Components

Unlike “MIL-spec,” these are wires and components that do not meet any aviation-related specifications. Although they are commonly encountered in airplanes throughout the owner-operated GA fleet, using them is dangerous for a few reasons – the first and most important of which is fire.

While any wire will eventually melt and/or burn if it gets hot enough, high-quality, approved aircraft wiring is far more robust. Commonly used in avionics retrofits, modern Teflon-insulated wire such as MIL-W-22759/16 (or equivalent) stranded wire and MIL-C-27500 cable that uses M22759/18 wire (or equivalent) for shielded wire is designed to withstand much more heat than wire purchased from your local auto parts store, hardware store or stereo equipment dealer.

This may seem like an obvious point, but often the logic is, “Well, I’ll just use a larger-gauge wire than it calls for and it’ll be okay.” While that approach may help keep the wire cooler under normal conditions, it will do little or nothing if the wire is subjected to flame externally or if the wire is shorted.

Additionally, when the MIL-spec wire does finally get hot enough to melt the insulation, it happens in a much more benign and predictable manner, thus providing more warning signs of failure (smell) than the consumer-grade wire.

I have personally witnessed a short in a length of wire that consisted of a section of MIL-spec wire spliced onto a section of automotive wire. The insulation nearly instantly burned off the entire length of the automotive wire, and then the glowing strands of the exposed wire in the run began to melt. The MIL-spec section, however, was completely unharmed.

Very thick acrid smoke that was extremely unpleasant to breathe filled the cockpit of the aircraft when that happened. Luckily, I was on the ground testing a new avionics installation and was able to immediately shut off electrical power, exit the aircraft, and ready a fire extinguisher. Had that event occurred in flight, however, it would have been a real emergency. At the very least, it would have meant the following:

- A total loss of electrical power in flight – because shutting off the master and not turning it back on is the first and most important thing you need to do in that situation.

- Smoke in the cockpit – How comfortable are you with evacuating a cockpit full of smoke at a moment’s notice while in flight?

- A possible fire – You do carry a fire extinguisher, right? Under what circumstances would you deploy it?

- Executing an immediate precautionary landing.

Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

JOIN HERE

Still have questions? Contact us here.