The Perils of Undocumented Maintenance

By Carl Ziegler, A&P/IA

We’re going to start this discussion at the top of the aviation system and work our way down to illustrate a problem that has become epidemic in our industry. During the years that I have participated in aviation forums, this specific issue has become more obvious, and I feel it is a good time to examine what I have observed. The name of this discussion and issue is “undocumented maintenance.”

In a nutshell, undocumented maintenance is, quite simply, work performed on an aircraft, system, or component that is not documented in a logbook or similar record that would normally indicate that work has been performed on that item.

First, let’s define the user group to which we are directing our discussion. 14 CFR Part 43.3, paragraph G, states – except for holders of a sport pilot certificate – the holder of a pilot certificate issued under Part 61 may perform preventive maintenance on any aircraft owned or operated by that pilot, which is not used under Part 121, 129, or 135 of this chapter.

What we’re addressing here is a pilot who is the owner of an aircraft and may be capable of performing some of the preventive maintenance items themselves.

So, you have done – or are about to perform – some preventive maintenance. What does Part 43 require you to do regarding documenting the work you have performed?

Section 43.9, which addresses the required maintenance record entries, states:

Each person who maintains, performs preventive maintenance, rebuilds, or alters, etc., shall make an entry in the maintenance record for that equipment consisting of a description of the work, the date of completion, and the name and kind of certificate held by the person performing the work. In the case of a pilot, this would be his signature and pilot license number.*

*In this example, I am assuming that the pilot and owner are one and the same.

Before I go further, I would like to remind readers that we are one of the very few industries and vocations that have a clear set of guidelines for how we build, maintain, and operate a component such as an airplane. Actually, let’s discard the word “guidelines” because we have regulations. The reason for this strict definition is that our industry is unforgiving of any deviation from our regulated standards of operation.

The Inspection Process

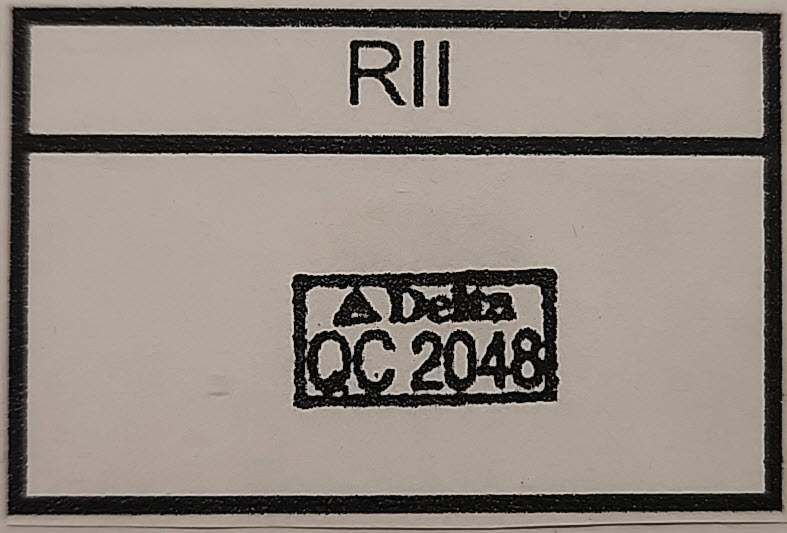

The photo of the stamp block you see may be familiar to a few people, but it is probably foreign to most observers. This stamp is issued at the airline level to trained and qualified aircraft inspectors who verify the safety, security, and conformity of work being performed on commercial aircraft. The stamp can be used during an “in-process event” (such as completing each step during an engine installation) or at the end of a work process to certify that the work was done according to the listed procedures. The final stamp at the end of the job indicates that the work has been inspected and completed satisfactorily (50 to 100 pages for an engine installation). The term on this box, “RII,” indicates the highest level of inspection requirements and signifies that the inspector who performed the verification was qualified for oversight of this specific event. I want to clarify that at no time does an inspector actually perform a maintenance function or mechanical work. This separation of maintenance and inspection duties is a fundamental factor in maintaining safety in our aviation industry. In simple terms, this is the top dog of inspection authority in the aviation industry. Next is an actual example to illustrate how undocumented maintenance can happen in the airline world. Occurrences are not always deliberate or accidental, as you will see from the following example.

Another Day at the Office

At the beginning of my shift, I was assigned as the inspector for a wide-body aircraft just completing the end of a 14-day check. I knew from my previous nights in this hangar that most of the major work had been accomplished on the aircraft and that we were within a day or two of releasing it for service. I did a casual review of all the maintenance items left to be completed and noted that I would probably have a quiet night with this aircraft. I took a stroll through the hangar, casually performing a mental preflight on the airplane to get a lay of the land for my evening. I went up into the cabin through the front doors and walked through the aircraft toward the aft. At the aft left main cabin door, one of the mechanics working that night had completely disassembled the entire inside of the door. I knew from the lack of paperwork in the office that all of the routine servicing and maintenance on this door had been completed and signed off/verified by another RII inspector. I questioned the mechanic about what he was doing, and he replied that they had found a discrepancy that had not been addressed and that needed to be corrected. In order to fix the issue, the door had to be disassembled again.

At this point, it was obvious that this mechanic had no idea that he had just put the previous inspector’s reputation and job on the line. He was working with none of the required paperwork, and his actions negated everything that the previous inspector had already verified and signed off.

I had a very stern conversation with this mechanic and told him to go downstairs and get the correct paperwork for reassembling the door so that the whole assembly could be re-inspected after he was finished. Had I not accidentally discovered this undocumented work in progress, the mechanic could have reassembled the door incorrectly—with consequences that could have ended up on the evening news. If, in fact, an issue arose after the aircraft left the hangar, the person held responsible would actually be the original inspector. The original inspector who signed off on this door, perhaps five days ago, had no idea what I had just witnessed. This is the danger of undocumented maintenance. The mechanic and his lead may have thought they were trying to get ahead of the process, but what they were doing was putting another inspector’s career in jeopardy.

Closer to Home

Here is an example similar to the above experience, yet a couple of tiers down in our world of General Aviation. The following is the accident analysis section from an NTSB accident report involving a Piper Cherokee Six back in May of 2018:

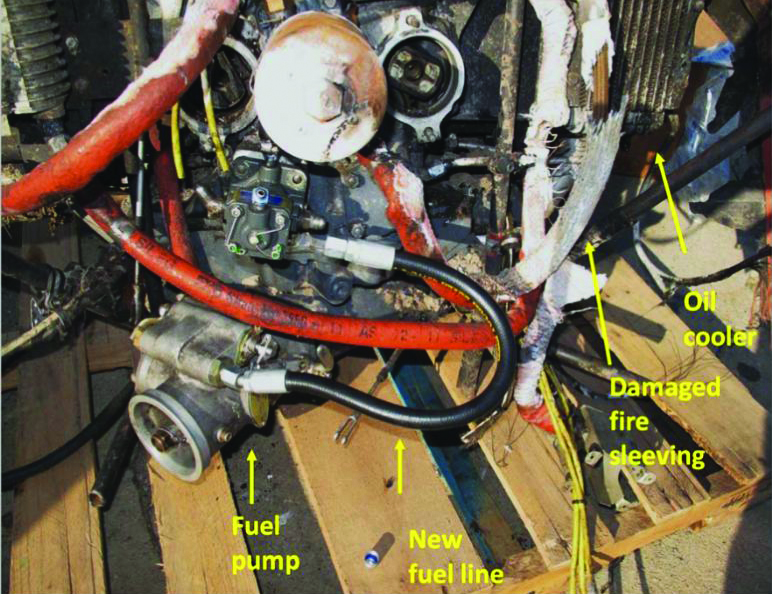

“The private pilot told a friend that he was having problems with his airplane’s engine and stated that he was going to taxi to the end of the runway and perform an engine run‐up. If the engine run‐up was successful, the pilot was going to conduct a short cross‐country flight and return. During takeoff, the engine experienced a total loss of power; the airplane subsequently impacted a wooded area about 1,100 feet south of the departure runway. Examination of the wreckage revealed that the airplane experienced an in‐flight fire, with the heaviest concentration of thermal damage on the aft right side of the engine compartment. The fuel inlet line from the fuel pump to the fuel servo was loose. According to the manufacturer, the part number of the inlet line installed on the accident airplane was not approved for aircraft use; however, aside from the part number, the approved hose looked identical to the unapproved hose, and the error likely could not be detected during an annual inspection. The airplane’s maintenance logbooks were destroyed during the accident, and the pilot performed some of the maintenance on the airplane himself (my emphasis); therefore, when and by whom the unapproved hose was installed could not be determined. It is likely that the loose fuel line allowed fuel to spray onto the exhaust system, which resulted in the in‐flight fire and the total loss of engine power.”

And one fatality.

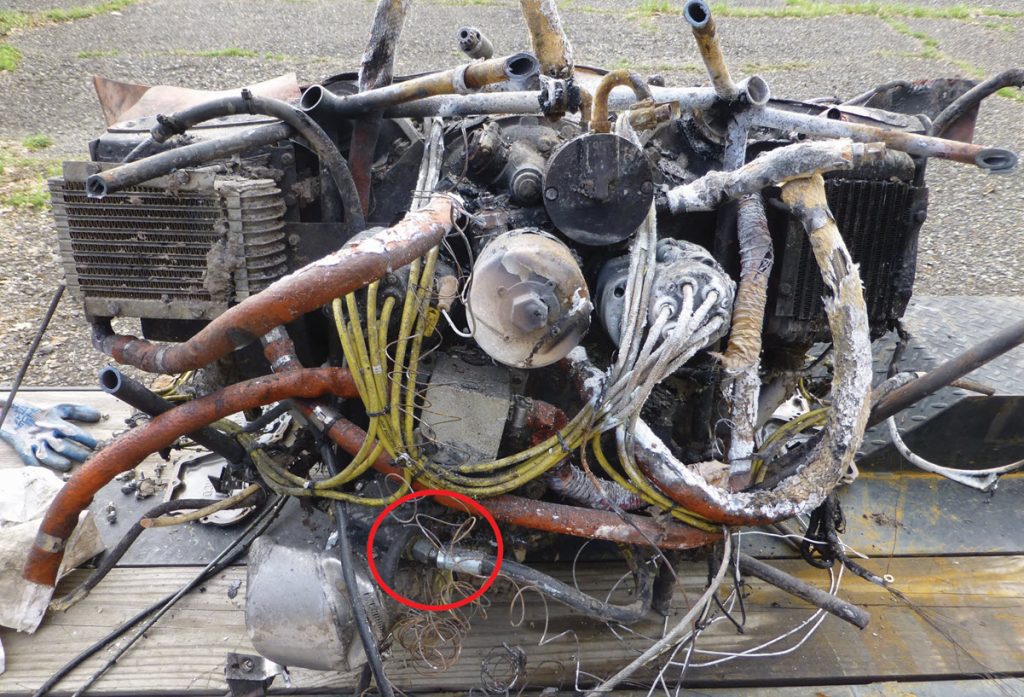

The photo of the firewall by itself should give you an indication of what was left of the airplane after it crashed. The other photo shows the location of the fuel line that apparently was changed by someone. The NTSB could not identify how, when, or by whom it was installed because the maintenance logbooks were destroyed.

Was this undocumented maintenance? It seems highly probable. Did the owner change it out because he had an issue with the original line? Can you see the parallel between a maintenance action by an aircraft owner and the issue that I uncovered with the mechanic working on an airliner’s door? There is one notable exception between these two scenarios. In the Piper accident, whoever installed the nonconforming part was obviously not qualified and did not understand the possible ramifications of his actions, in addition to not seeking out a qualified person for a final inspection.

In my airline example, while the system failed the mechanic, we have procedures in place to double-check all critical work. Fortunately, the NTSB did not fault any maintenance personnel who had worked on the Cherokee aircraft, as they determined it would have been impossible to identify that hose in its installed condition. Whether or not there were any entries in a logbook, we will never know, as they were destroyed. (Another pot of coffee discussion.)

The Takeaway

Under 14 CFR regulations Part 43 and 91.403—governing the maintenance and operation of aircraft—the owner is legally required to ensure that the aircraft is in a legal and safe condition. The legal aspect is governed by who can work on an airplane and take responsibility for the work performed. If you are attempting work that is legally required to be accomplished by a licensed A&P — and that mechanic is not by your side—then you are operating outside the limits of your authority.

I constantly see owners asking questions about work procedures on various Internet sites. Many of these queries are definitely outside what is permitted under preventive maintenance. I would like to think that these are isolated events, but these scenarios are becoming more common. Owners need to keep in mind that when they choose to work outside the scope of limitations on their own airplane, they are possibly jeopardizing their own safety as well as the livelihood of other people who may have worked on the aircraft.

Compliance Matters

When a shop or an IA certifies that an aircraft is in compliance during an annual inspection, we have no knowledge of what an owner may do to the aircraft once it leaves the shop. I have no control if an owner wants to take the engine off his airplane when it is out of my sight and then put it back on without any help. I would like to think he would record that entire engine removal and replacement in the logbook, but it’s safe to say he would not. I’m smart enough to know that there are owners out there who are extremely mechanically inclined, and those are the people I certainly enjoy working with. I hope that, as an owner, you can find (or have) a good mechanic or shop that works with you and helps you maintain your aircraft legally and in safe condition.

Post COVID, we have lost many mechanics and shops around the country, which may encourage owners to attempt more maintenance outside of regulatory limitations. Unfortunately, I also know from experience that the competence of maintenance technicians entering our industry varies widely, and this is another issue that needs to be addressed by the FAA. I am not going to hold my breath on that issue, so perhaps we can save that discussion for another day.

Where Do You Fall

So, given the scenarios above, which part of the loop do you operate in? Regulated or the Wild West?

While the choice is yours as a pilot-owner, our path is set by defined regulations. Undocumented maintenance is a problem that spans our entire industry—just ask Boeing.

Keep your seat belt fastened.

Carl has close to 50 years of continuous experience working as an aircraft technician and 38 years as an IA. In addition to GA, he has acquired over 38 years of airline experience with Northwest and most recently with Delta, finishing his last 13 years of airline service as an aircraft inspector. He currently flies a 1976 Cessna 172N.